Inshore fisheries law and governance is a complex topic that requires consideration of Fiji’s unique culture and historical background. In this overview we consider the evolution of Fiji’s inshore fisheries law and governance context, as understanding it is an important tool in the management of Fiji’s inshore fisheries . We aim to describe this rich nuanced system that is based on a balance of customary rights and centralized regulation.

This is a summary of a presentation provided to the Fiji Environmental Law Association and the Department of Fisheries, Coastal Fisheries Management Legal Development Forum held at the Tanoa Hotel, Suva 10-12 February 2016.

Suva based lawyer, Nancy Loaloa, undertaking community training and explaining Fiji's maritime boundaries, Macuata, November 2015

Recently, I have been lucky enough to visit the province of Macuata, Vanua Levu twice. The second time, I was stranded for an extra week as cyclone Ula delayed the ferry. While my wife was quite annoyed with me, I had a valuable opportunity to spend time around some remoter coastal villages in the remoter spots in Macuata. I spoke to many people who rely on their inshore fishing areas for food and for money, and who have a good understanding of what is happening in their fisheries areas. They understand that their fisheries are under threat because they can see it happening, and a commonly reported concern was that fish were getting smaller and scarcer with some species that were common in the past being rarely seen today.

A major issue or concern involves middlemen who send drivers from Labasa along the Macuata coast to collect everything from the village gate and these middlemen offer low prices. Individuals from the coastal communities need money and so they sell for low prices. This practice is causing conflict in communities, as not everyone agrees with the harvesting of communally owned resources for quick financial gain. It is likely that the commercial pressure being brought by the middlemen is eroding traditional management efforts as well as traditional governance structures. The law, at present, doesn’t regulate middlemen, and the legal burden falls on the fishermen and communities who are regulated by the Fisheries Act, 1942.

In discussions around inshore fisheries and in looking for better management of resources we need to be mindful of the pressures on communities. It is also notable that many of the people I spoke to expressly acknowledged the assistance and the help that they receive from the Department of Fisheries and various NGOs that work in this area.

We hope that this overview will bring out the important role that the Department of Fisheries plays and how they work with and integrate with other key governance institutions like the iTaukei Affairs Board.

I also expressly acknowledge, Ratu Joni Madraiwiwi, who is with us today and has been the Fiji Environmental Law Association’s patron from its beginning in 2008. His work often takes him out of Fiji, which is always to Fiji’s loss and to another country’s gain. Ratu Joni has always provided moral support and guidance to FELA, and we are honoured to have him with us.

While I hope that I can do justice to Fiji’s unique cultural heritage and systems of both traditional and modern governance I remain humbled by the people that we have in the room, and I apologise in advance because this is just an overview and as such it cannot do justice to an area that I remain acutely aware is: complex, often controversial and crosses into cultural issues. I acknowledge that an explanation of the law cannot explain what resource rights mean to iTaukei communities.

Inshore Fisheries

In recent times, when officers from the Department of Fisheries refer to inshore fisheries, they mean the traditional fishing grounds that are mapped in accordance with a process set out in the Fisheries Act, 1942. These traditional fishing grounds cover foreshore areas, vary in size, but generally extend from the high tide mark to the outer edges of the Fringing reefs. These traditional fishing grounds are almost all within Fiji’s archipelagic waters, and completely within Fiji’s territorial waters. They are known in Fiji as the qoliqoli. The Fisheries Act recognises the usufructuary rights that are held on a communal basis in favour of the traditional iTaukei groups known as Yavusa (loosely meaning tribes) and equate to rights to harvest fish for subsistence purposes.

Outside qoliqoli areas or beyond the fringing reef are the remainder of Fiji’s archipelagic waters, Fiji’s territorial sea and EEZ. In relation to these areas of ocean the Offshore Management Decree regulates and governs all fishing activity.

Therefore, for our present purposes, and in accordance with the Department of Fisheries approach, when we refer to ‘Inshore fisheries’ we mean fishing within qoliqoli areas.

The evolution of Fiji’s inshore fisheries law

The changes to, and evolution of, Fiji’s law and governance system as it applies to inshore fisheries reflects the introduction of common law and the growing impact and importance of international law.

Prior to the colonial era, there was no written system that recorded rights to land or the sea, and the traditional understanding was based on collective or communal ownership. While in pre-colonial Fiji there were chiefs, and a traditional hierarchy that has been robust enough to stand the test of time, this did not extend to ownership over land or the sea in a Western and individual sense. This was not a feudal system, but one where the chief was a custodian of authority, but everyone owned the resources together. A key feature of the traditional governance system is that no distinction was made between the resources of the land and the sea in terms of the communal rights to harvest the bounty of both.

Community members may have had traditional roles or duties within specific communities, for example to supply the fish at a community event, but this didn’t mean that only a section of the community were fishermen. It is likely that within coastal communities everyone utilised traditional fishing grounds as and when required.

Within these communal fishing areas there were traditional forms of fisheries management, and traditional fishing practices that worked well. Particularly notable, were tabu areas. Many of you are familiar with the word tabu – and will understand it better than I do – and the point is that they may have been used to mark or commemorate an event such as the death of a Chief, but these practices are likely to have also had an impact in terms of fisheries management.

In this pre-colonial era it is likely that fish were not in short supply, and that it was well understood that fish were a common pool resource, meaning that it was understood that fisheries resources belonged to everyone within the group or community.

This traditional treatment of qoliqoli areas, and particularly the concept of communal ownership is still relevant because traditional governance structures were, to an extent, respected by the British and were to some extent codified and incorporated within the current governance system, and it means that the understanding of communal or group rights persists to this day in terms of inshore fisheries.

When Fiji was ceded to the British Empire the colonial administration brought with it 19th century views related to the law of the sea, and the use of resources.

This understanding was based on some fundamental premises, which included:

- Fish stocks were inexhaustible, and wild fish belonged to no one. This led to an attitude of de minimis regulation

- The sea should be kept open – freedom of the seas (mare Liberum). This suited the British as its navy was so powerful, and the last thing the Empire wanted was for any State to restrict access to the ocean. While in the past the odd King of England had tried to argue the other way to protect British domestic fishing operations, including notably Scottish oyster beds, the prevailing view by the time that they got to Fiji was that the seas should be free and open to all.

But, as part of the 19th century system Britain also brought their system and ideas of property ownership. This system was very different from the traditional Fijian systems ownership, because the British system had evolved from a feudal system based on individual rather than group ownership.

The British system of property ownership, amongst other things:

- Introduced a written system based on titles;

- Is based on the ability to occupy and enforce that occupation against all others

- Did distinguish between the sea and the land, because the British determined that because the land could be occupied that occupation could be enforced against the world, while the sea according to the British, other than a thin strip close to the coast could not (and as mentioned the guiding philosophy was to protect the freedom of the seas).

Fiji, under colonial rule found that new rules and laws introduced concepts that had not existed previously. Already mentioned was the important principle of freedom of the seas and navigation, and another was the cannon shot rule which meant anything within 3 nautical miles of the coast would become territorial waters, owned by the State because the State could exercise control and impose rules that were good against the rest of the world in terms of who could access the territorial sea. This extended the sovereignty of a State over 3 nautical miles and the State could solely determine how the resources within that area of territorial sea could be used.

At the same time anything outside that 3 nautical mile zone was effectively the high seas and was beyond State sovereignty as confirmed in the famous contemporary case of the Behring Seals Arbitration between the US and UK, where the US failed in its claim to control and manage a seal colony outside a 3 nautical mile zone.

The cannon shot rule was based on the understanding that a cannon could be used to propel a cannon ball into the side of any foreign boat that was reckless or unfortunate enough to come too close to the British coast, and it meant that an area of sea could be effectively occupied on the basis that through the use of a cannon others could be effectively excluded from it.

RML 64 pounder is an example of a coastal defence cannon that was in service between 1870-1902 and fired a 32 pound cannon ball to ensure Britain and its colonies could enforce the cannon shot rule

The British also introduced the common law to Fiji, and a significant part of the common law relates to wild animals and determines that wild animals in their wild state cannot be controlled and therefore cannot be owned. This principle is known as ferae naturae, and it applies to wild fish in their uncaptured state. Ownership of the fish only passes on capture within the law. This principle continues to this day, and it explains why if we want to protect wild animals specific legislation needs to be made. In essence, people do not own wild animals so, if we want to protect them in a common law system, like Fiji, the State has to enact law to protect them from being killed or hunted. We will come to the Fisheries Act and Regulations and other legislation like endangered animals Act in due course.

The British also brought with them contagious diseases and lawyers.

One of the first documents that the lawyers drafted was the Deed of Session in 1874. As is so often the case, once you get lawyers involved you also get disputes. The Deed of Cession is no exception to this rule, and the meaning of the Deed of Cession has been subject to dispute until today. A fundamental dispute stems from the fairly well accepted view that at the time it was explained to the British by the assembled High Chiefs before they signed the Deed of Cession that the High Chiefs of Fiji could not pass on title to the land and the reefs because the land and the reefs did not belong to the Chiefs under the traditional Fijian system. This seems to have been fairly well understood at the time by the British too, and particularly by Sir Arthur Gordon who campaigned for Indigenous Fijians’ land rights upon his return to Britain. It also explains why the British later introduced a system of land ownership that made iTaukei titles to the land inalienable and has retained a majority of land titles in iTaukei name, amounting to almost 90% of Fiji’s total land area.

But the key point for the purposes of inshore fisheries regulation is that while the British had a system for ownership of land and titles, they had no system for the ownership and titles of marine areas, and as noted, the British were keen to apply what had then recently become a fundamental principle of international maritime law, the freedom of the seas or mare liberum.

To put this another way there was no system of marine tenure that the British brought with them that could be imposed on Fiji (beyond the cannon shot rule). As a result, what then developed was a system of marine tenure that is unique to Fiji and is a mix of traditional rights and modern law.

It is likely that the British Colonials, who were somewhat obsessed with the occupation theory of property (think an Englishman’s home is his castle), observed that iTaukei were occupying and using their traditional fishing grounds. Additionally, the Colonial administration seems to have taken a divisive policy towards iTaukei and the indentured labourers that they brought in from India. This is likely to have manifested in a general policy of keeping iTaukei within traditional village environments, and community structures while indo-Fijians and others were settled in towns and rural areas outside villages.

In this context the Colonial administration introduced legislation that recognised some protection of traditional rights, and in relation to inshore fisheries this culminated in the Fisheries Act 1942, which was enacted to regulate the activity of fishing in Fiji waters. A key part of the Fisheries Act, was the express recognition of traditional fishing grounds, known as qoliqoli.

The Fisheries Act (section 13) created a statutory body called the Native Lands and Fisheries Commission (now called the iTaukei Lands and Fisheries Commission) and pursuant to a process set out in the Fisheries Act this Commission undertook enquiries from the 1950s onwards that led to the recording of the boundaries of qoliqoli areas. These records are still retained by iTaukei Lands and Fisheries Commission which is located within the iTaukei Affairs Board.

The qoliqoli areas reflected something unique about Fiji. This is: while the Colonial administration ensured that the inshore waters or coastal waters are all owned by the State, it recognised the importance of traditional fishing rights to iTaukei. It means that they provided some sort of special recognition of the importance of fisheries resources to the iTaukei.

While the boundaries have generally been accepted over time, there are sometimes disputes relating to the boundaries that can create discord and confusion. This is because the recorded boundaries were based on memories and understandings, and now when disputes over the actual boundaries arise, they are settled by the iTaukei Lands and Fisheries Commission with the production of the official maps.

We will address the law and governance behind qoliqoli areas in more detail later, but at this point it is important to recognise that the legislation does not convey ownership of the areas, but through a mix of law and practice has vested certain rights in the relevant and registered communities that are held still on a traditional and communal basis.

The development and impact of International Law of the Sea

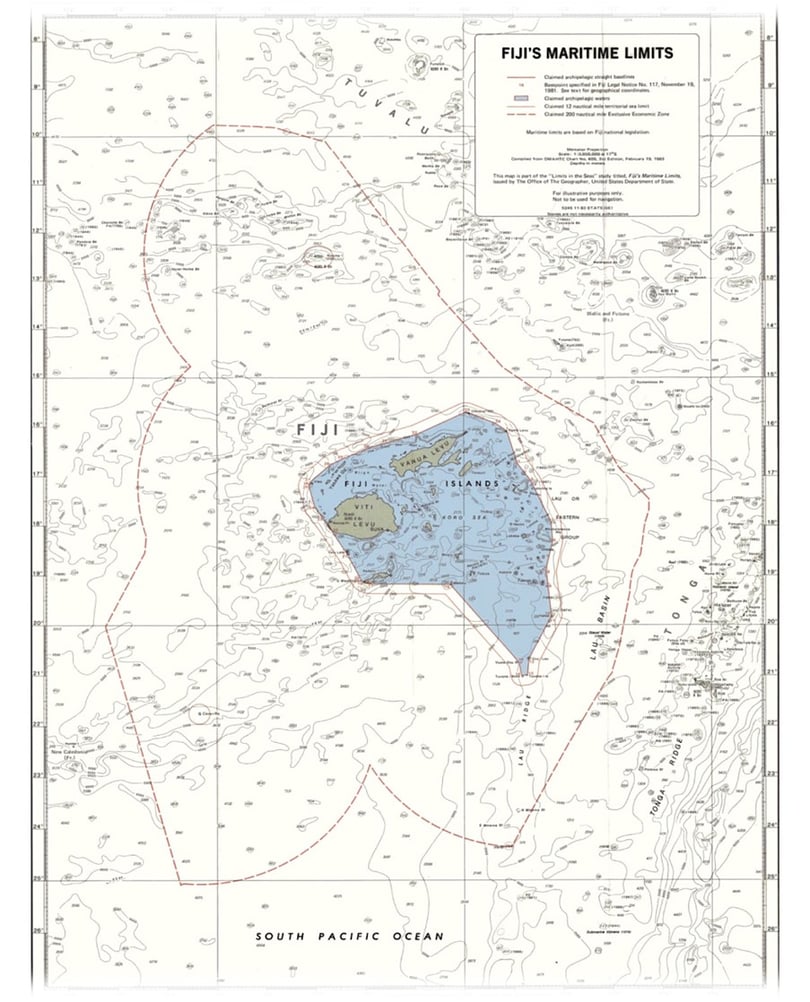

Relatively recently, and after its independence Fiji has played a significant role in the development of positive law relating to the law of the sea. We only mention this briefly here, because the main developments relate to the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), and developments of new maritime zones, that are reflected in Fiji's Maritime Spaces Act.

These developments reflect the further enclosure of ocean spaces, that have happened because in the international sphere, States want to exercise more control over the waters that surround them, and because it is thought that more control by States will result in better management of natural resources in those oceans spaces.

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) is an international convention that is signed by States that then recognises that State’s authority and sovereignty over vast areas of ocean space in accordance with international law. Fiji was the first State to sign UNCLOS.

But these additional areas of ocean space must be positively claimed, and through UNCLOS and the operation of international law Fiji gained a positive right to lay claim to a larger area of ocean space and the natural resources contained in that area.

Below is a map that shows the boundaries of Fiji’s archipelagic waters (all shaded in blue), Fiji’s territorial sea which is now 12 miles from the boundaries of its archipelagic waters and Fiji’s claimed EEZ (the outer lines) that can be claimed up to 200 miles from the archipelagic baseline but which is also delimited by other claims by other States.

Within the marine spaces context, it is worth noting that the qoliqoli boundaries do not correspond with any legal definition in UNCLOS, because they are a product of Fiji law only. There are approximately 410 registered qoliqoli areas that surround Fiji and each one is registered to a different Yavusa or grouping of Yavusa. As mentioned detailed maps can be obtained from the iTaukei Land and Fisheries Commission. The exact boundaries are important for fishing permits and licensing for those who want to fish commercially within a qoliqoli. This is because a permit is required for each qoliqoli, and a permit does not entitle the fisherman to go to other qoliqoli areas.

Fiji’s legal and governance system is characterised by centralised control

.Many countries have devolved powers that provide ability to make laws and regulation powers to regional bodies. In Fiji's case, there is still a traditional form of governance, and we have Provincial Councils, where institutions like the Taukei Affairs Board (iTAB) within the Ministry of iTaukei Affairs, and Divisional Commissioners from the Ministry of Rural Development meet. While these places are important for consultation and discussion, these bodies have no jurisdiction to make law or legal regulations. They work with and consult with communities, but any laws, including even village by laws must go back up the chain of command to at least Ministerial or Cabinet level.

An important example of this is the creation of restricted fishing areas or what could be termed Marines Protected Areas (MPAs) under section 9 of the Fisheries Act. We address the creation of MPAs in a separate presentation and in more detail, but we think the important point to remember is that Fiji’s formal system of law and governance is characterised as one of centralised control where law is made by Ministers through delegated authority in legislation. Section 9 of the Fisheries Act enables the Minister to make specific regulations that includes the creation of marine protected areas within traditional fishing grounds.

Of course, Fiji's system of centralised control does not prevent individual communities from imposing traditional fisheries management methods in relation to their fishing efforts and it is this power is what has been so effectively harnessed by Fiji’s Locally Managed Marine Areas (FLMMA). Indeed FLMMA has its own community implemented version of MPAs which are called tabu areas, and in these community designated areas fishing activity may be subject to varying levels of restriction determined by the communities themselves. However, it is important to bear in mind that community created tabu areas, are not created by operation of law, and are only enforceable against those outside the community to the extent that the tabu areas are recognised as conditions in any fishing licences. We address conditions in fishing licences in more detail later. While this is a complex area, any disadvantages of a tabu area not being legally recognised should be weighed against the control that they provide to communities to decide for themselves what fisheries management tools are most effective in what they perceive as their traditional fisheries grounds.

Fisheries Act, 1942 and Fisheries Regulations

The Fisheries Act and Fisheries Regulations are the primary legislation regulating inshore fisheries in Fiji. It controls fishing in inshore areas through a permit and licensing system.

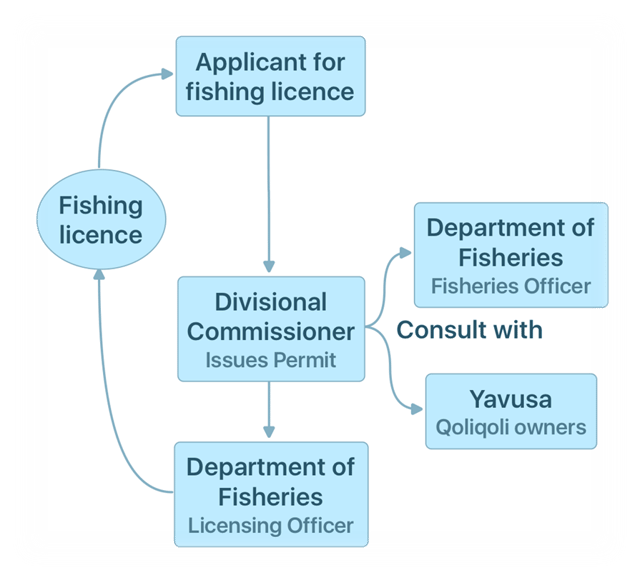

The first important thing to note is that the permit and licensing system are distinct because they are issued by different people. The permit is issued by the Divisional Commissioner pursuant to a consultation process set out in the Fisheries Act which requires the Divisional Commissioner to consult with the relevant Yavusa who hold the traditional fisheries rights and the Department of Fisheries. Once the permit is granted, the actual licence is issued by the Dept of Fisheries.

For inshore fishing areas the following things are important to note:

- Anyone (iTaukei or not, from that qoliqoli or not) who wants to fish commercially in a qoliqoli area – must have a permit from the Commissioner and a licence from the Department of Fisheries.

- The permit process is set out below. In short, the application must be made to the Divisional commissioner who must consult with the iTaukei community and the DOF Officer.

The graphic below explains how this system is intended to work:

The following points are worth noting in relation to this process:

- There are administrative law underpinnings to this licensing process, as the legislation requires consultation and a reasonable decision. The lawyers in the room will understand this. The Commissioner cannot make an illegal decision, must follow the process of consulting and take into account relevant and ignore irrelevant considerations.

- iTaukei communities do not need a permit to fish for subsistence within a qoliqoli registered to the Yavusa that they belong to, and this is what is meant by their fishing right in their area.

- But this right is limited because there is a general public right to fish with a line or a portable trap that can be operated by one person.

- As part of the permit and consultation process the community may seek conditions on the licence that are often repeated in the Department of Fisheries licence. In this way the community can control fishing or impose community determined tabu areas.

- In practice, the Fisheries Officers and the Commissioner works closely with the Community reflecting the respect and understanding between them.

The Fisheries Regulations control what can and cannot be done by anyone who fishes in inshore areas. Fishing without a licence is an offence and there are comprehensive regulations that relate to minimum sizes of fish species that may be caught. Also regulated are fishing methods, types of fishing activities and types of fishing. From time to time the Fisheries Regulations are updated with the addition of new regulations, and it is likely that further updates will have to be made to support the sustainable management of Fiji's inshore fisheries.

All prosecution powers rest with the State, being the police, Director of Public Prosecutions and the Judiciary. The police may be assisted by Fisheries Wardens who are from the Community but appointed under the Fisheries Act.

Conclusions

Fiji’s unique law and governance system creates and shares rights between communities and the State, and in terms of food security and fisheries management the big challenge is how to make good decisions to assist with sustainable fisheries management. A starting point for good decisions is a close relationship between communities and the Department of Fisheries who can lend their expertise to management. The assistance and expertise of NGOs is also invaluable in this context, and communities through FLMMA are also able to create fisheries management initiatives that are likely to find broad support amongst stakeholders.

Communities are vitally important in this role because they are present in the remote areas and are the traditional managers of the resource. While we have seen the law and governance system came from 19th century Britain, what has emerged over time represents a mix of traditional and modern law.

How Fiji has achieved this balance deserves attention because in recent times, fisheries management experts from around the world have found themselves grappling with the difficult question of the allocation of fishing rights within nation States. But, Fiji has, through an evolutionary process briefly discussed here, ended up with a system where those rights are balanced between the State and communities. This system has evolved through respect and understanding, that recognises the traditional system and the recognition that successive governments have given to it over the years. Notable examples of this respect include compensation payments for loss or waiver of fishing rights.

However, an important point to note is that while communities have rights, if the resources are not managed then any compensation payments are likely to be less for the loss of those rights. Put simply what is the use of rights to resources, if the resources don’t exist?

Therefore, the important question is how can fisheries management systems build on this law and governance context? Fish remain a common pool resource and in resource use terms without good management people will try and take fish before the next person can. This leads to a race to the bottom so famously described by Hardin's Tragedy of the commons.

To avert the tragedy of the commons, some call for stronger private property rights, as they link private property rights to the economic theory that if you have a vested interest you will look after the resources better. But not everybody agrees with this, and to our mind, the key point for Fiji is to adopt fisheries management systems that respect Fiji's unique context and build on communally held ownership rights.

Perhaps part of the answer for Fiji is to embrace the law and governance system, promote understanding of the issues, and bolster the existing efforts of co-management of fisheries resources between the State and the Communities. After all this is a food security issue for Fiji and good management of the resources will benefit both the State and the traditional communities.

I would like to thank you for listening and particularly thanks to Kiji, Mela, Terence and Patricia from the Fiji Environmental Law Association (fela.org.fj) for organising this conference. Perhaps over the next 3 days we can start working out how we can all assist with the promotion of good fisheries management. I expressly acknowledge the presence of Director of Fisheries – Aisake Batibasaga and key fisheries officers like Margaret Tabunakawai and the rest of the Department of Fisheries, who have supported this workshop, and who have the hard jobs. Finally I thank the representatives from the iTaukei Affairs Board, Department of Forestry, and the Director of Public Prosecutions, and the Ministry for Strategic Planning, National Development and Statistics, Ministry of Lands, and Maritime Safety Authority of Fiji for sending delegates to attend this conference.

Please note:

This legal bulletin is provided for general information purposes only and it is not, and should not be relied on as, legal advice.