Seabed mining is a new industry that seeks to exploit the value of metals on or in the seabed. The drivers for this industry include the rising demand and costs for the metals in question. Many of the potential mining sites are found under the Pacific Ocean in areas beyond the national jurisdiction of any State. This area of deep seabed beyond national jurisdiction is defined by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea ("LOSC") as “the Area”.

This new industry is intended to be regulated pursuant to LOSC by the International Seabed Authority (a body created by LOSC). The International Seabed Authority will issue licences to Applicants that are sponsored by nation States (sponsoring States). The licences will be issued subject to conditions that are intended to protect the marine environment, however, sponsoring States are themselves subject to duties under international law and amongst other things are required by LOSC to have their own legislation in place to regulate the mining companies that they sponsor. If this legislation is not in place or is inadequate then sponsoring States will not meet their international law duties, will incur legal risk, and this new industry will not be properly regulated.

In this bulletin, we set out what is known from a legal and governance perspective about seabed mining in the Area, describe how the international regulatory framework is supposed to work and review the results of a recent legal analysis that demonstrates the legal framework is not yet in place to meet various requirements under the international legal framework. We respectfully suggest that this legal analysis supports the view that seabed mining is not, as yet, ready to proceed as an effectively regulated industry in accordance with international law.

About this legal bulletin

This legal bulletin is a summary of a presentation provided at the School of Marine Studies (USP) on Friday 22 November 2019 as part of a panel discussion to discuss seabed mining. This panel included Dr Greg Stone, chief ocean scientist of DeepGreen (a company that is active and interested in mining deep seabed), Dr Russell Howorth of the Legal and Technical Commission of the International Seabed Authority, Dr Elizabeth Holland of USP and Professor of Climate Change, Dr Claire Slatter a Fiji activist and academic, and the author.

There are arguments for and against seabed mining

Proponents for seabed mining argue that these metals are essential for a shift to a greener economy that includes electric vehicles, and suggest that the mining activity will cause less harm to the environment and to people than land based mining activities, and will result in financial windfalls for States (including Pacific Island States) that get involved. During the presentations at USP, Dr Stone, a well known marine scientist expanded on these arguments for seabed mining and put forward a forceful argument that the metals were essential to transition to a greener economy with a particular emphasis on electric vehicles to replace vehicles with internal combustion engines. Dr Stone also focused on the mining of certain poly-metallic nodules which he suggested could be harvested with minimal disturbance and impact.

Those concerned about or against deep seabed mining point out how little is known about the deep seabed and the potential adverse consequences of seabed mining on the marine environment and unique ecosystems that we are only just learning about. This concern is reflected in a call for a pause to allow more scientific research to be done. In support of more science before mining, various international environmental law principles are cited including the precautionary approach/principle. They question the wisdom of starting another industrial/exploitative activity in the ocean at a time when ocean health is already impacted by a host of other activities and climate change. Dr Holland during the panel discussion raised a concern relating to the amount of stored carbon in the seafloor that could be released and Dr Slatter suggested that although one form of seabed mining may be less harmful than another form of mining or seabed mining, once the door is opened for seabed mining, other more harmful forms of seabed mining would likely follow.

This legal bulletin does not address the arguments for and against seabed mining or whether certain types of seabed mining are less potentially harmful than others. This bulletin considers the specific question of the legal risks for sponsoring States that may be interested in engaging in seabed mining or as a sponsoring State for seabed mining.

Seabed mining within national jurisdiction

Seabed mining has commenced within areas of seabed that are within national jurisdiction. Japan and Papua New Guinea have mined (Japan) or attempted to mine (PNG) areas of their seabed within their national jurisdictions.

If mining takes place within areas of seabed within national jurisdiction, for example, on or within the seabed within a State’s Continental Shelf, or beneath its Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), territorial sea, archipelagic waters or internal waters, then that State will regulate the mining activity in accordance with its national laws and international duties and responsibilities.

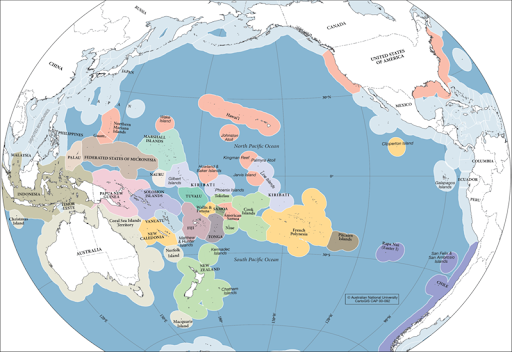

The map below demonstrates how large areas of national jurisdiction are in the Pacific - as the coloured areas of oceans show the EEZs in the Pacific.

In relation to mining within areas of national jurisdiction it is the nation State who will issue the mining licence, and both set and enforce any rules or laws that the licence is subject to. Any nation State that is interested in exploring seabed mining within its areas of national jurisdiction, remains obligated to its international law duties including duties pursuant to LOSC and should base any decision to permit mining on, amongst other things:

- The best available science / common concern for humankind (emerging concept)

- Best environmental practices / EIAs and EM (environmental monitoring)

- The precautionary principle / Transboundary Harm / Free Prior Informed Consent of citizens/indigenous

The State should also consider the question of effective implementation as effective regulation of any mining activity requires resources.

Further, at the present time, the science for seabed mining is uncertain, regardless of where it takes place. This is likely to have been one of the reasons that Fiji has announced and included in its Climate Change Bill that there will be a 10 year moratorium on seabed mining - this means on seabed within national jurisdiction and as the Bill is currently drafted - excludes exploration.

Seabed mining in the Area

Seabed mining for exploitation rather than exploration has not yet occurred in the Area. Amongst other things, the International Seabed Authority has not yet completed its regulations that it will require all sponsoring States to meet before it issues a licence. It is understood that ISA is currently developing these regulations for the exploitation of marine minerals in the Area which will include regulations for liability for damage and these are supposed to be released at the end of 2020.

This map demonstrates the scale of potential mining sites that have been identified in the Pacific Ocean, and it should be noted that these sites are both within national jurisdictions (within EEZs that are shaded in darker blue) and outside areas of national jurisdiction (the Area).

.png)

The International Seabed Authority’s role - regulating seabed mining in the Area

When seabed mining is proposed or takes place on the seafloor in the Area (beyond national jurisdiction) then, in accordance with LOSC - ISA is responsible for regulating the licensing of these mining ventures.

ISA therefore regulates, organises and controls seabed mining activities in the Area, and, as part of its duties must:

- Ensure the orderly, safe and rational management of the resources of the Area, for the over-all development of all countries

- Promote and encourage marine scientific research

- Ensure effective protection for the marine environment from harmful effects

- Ensure effective protection of human life

- Promote the effective participation of developing States in activities in the Area

- Share knowledge with developing countries

- Develop international law of the Area

- Provide for the equitable sharing of financial and other economic benefits derived from activities in the Area

- Receive and distribute revenue from exploitation of continental shelves within national jurisdiction (but beyond 200 miles).

ISA duties therefore include, but are not limited to:

- Creating the rules to ensure effective protection of the marine environment from harmful effects which may arise from seabed mineral activities in the Area.

- Acting on the behalf of humankind as a whole.

The Applicant for seabed mining activity in the Area - and its legal duties and liability

Any Applicant interested in deep seabed mining in the Area must apply to the International Seabed Authority and must be a State signatory to UNCLOS or be sponsored by such a State.

ISA is therefore, effectively, a licensing body as any successful Applicant will be granted a commercial licence to explore or to mine/exploit by ISA. ISA will also determine the preconditions to and conditions for any mining licence.

However, ISA remains only the Licensor, meaning that provided ISA discharges its duties in issuing the mining licence, ISA will not take on any liability for the mining activity. This is because the liability is assumed by the Applicant/Sponsoring State who, if it wants to meet its own international duties under LOSC must:

- Enact comprehensive (ISA approved) national legislation; and

- Effectively implement this legislation.

The specific Duties and Legal Risks for Sponsoring States

The specific International law duties (and therefore risks) arise for Sponsoring States by operation of the LOSC, and in particular two Articles of LOSC. These are:

- Art 192 of LOSC - general duty on all States to protect and preserve the marine environment;

- Art 235 of LOSC - States must meet this duty or will be liable in accordance with International law - This means each sponsoring State must:

- Ensure recourse for prompt and adequate compensation for any damage caused by the pollution of the marine environment

- States must cooperate for prompt assessment of damage/dispute resolution.

It is clear and accepted that sponsoring States must have suitable national legislation in place to meet these international commitments in Articles 192 and 235 of the LOSC.

In addition, the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS - a judicial institution created by the LOSC) has published an advisory opinion (case number 17 - Responsibilities and obligations of States with respect to activities in the Area) that has considered the responsibility of the sponsoring State and has provided that the sponsoring State must exercise high standards of due diligence to secure compliance with the terms of the contract awarded by ISA. Further, the advisory opinion from ITLOS mentions the precautionary approach and the obligation to undertake environmental impact assessments which it describes as a “general obligation under customary law”.

How many sponsoring States are there at the present time?

While none of the sponsoring States have so far been issued with an exploitation/mining licence, 20 different sponsoring States have shown an interest in obtaining an exploitation licence for the Area and have been issued with exploration licences by ISA.

To date, ISA has issued 29 exploration contracts to 20 different contractors/20 different sponsoring States as follows:

- Russia and China have each sponsored four contracts

- Korea has sponsored two contracts and one pending contract

- Japan, France, India, Germany and the United Kingdom have each sponsored two contracts

- Poland has sponsored one contract as part of the Interoceanmetal Joint Organization (IOM) consortium and one other pending contract

- Belgium, Tonga, Nauru, Singapore, Kiribati, the Cook Islands and Brazil have each sponsored one contract

- Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Cuba, Slovakia and Poland are each co-sponsors of the consortium contract.

Given that sponsoring States should have effective national legislation in place to regulate seabed mining, it is possible to examine the national legislation of the 20 sponsoring States that have so far been awarded exploration contracts by ISA. Fortunately, this challenging legal task has already been undertaken by the Center for International Governance and Innovation (CIGI).

CIGI has published the results of this legal review - in a paper entitled “Sponsoring State Approaches to Liability Regimes for Environmental Damage Caused by Seabed Mining” authored by Hannah Lily. Hannah is a UK qualified solicitor and legal expert on regulatory law who specialises in seabed mining and has held the position of legal adviser at the Commonwealth Secretariat in London.

Hannah’s paper provides a careful and thorough analysis of the national legislation of the 20 sponsoring States and uncovers some startling gaps, issues and concerns. This is a screenshot of the cover of CIGI's publication that can be found online:

CIGI's report authored by Hannah Lily which includes a thorough review of sponsoring States' legislation, and includes advice to ISA can be found: here

Summary of CIGI’s findings after examining the laws of 20 sponsoring States

10 sponsoring States had no targeted national legislation to regulate seabed mining

As of October 2018, CIGI found that of the 20 sponsoring States with exploratory licences, only 10 had targeted national sponsoring laws in place. This meant that 13 exploration contracts had been granted by ISA to States with no relevant laws in place and therefore those States were not meeting due diligence responsibilities under LOSC and were therefore exposed to any damages arising from the contractor’s activities.

This raised issues regarding whether ISA is undertaking its oversight function properly and led CIGI to question whether the ISA Secretariat has capacity challenges to assist sponsoring States with legislation.

The laws that are in place leave questions of what can be claimed in doubt

CIGI concluded after reviewing the laws that are in place that they contained scant coverage regarding what type of relief could be claimed by an affected claimant. The general observation was that they did not provide much detail regarding what type or degree of harm is actionable nor did they expand on the standard of liability that would be applied to a contractor by the sponsoring State’s national legal regime. It was noted this was made more difficult to determine because many of the national laws are in different languages and translations had to be relied on.

This led CIGI to pose significant legal questions relating to:

- The amounts of damages that could be claimed and whether damages would include restoration

- How the damages would be assessed

- Whether funds could be awarded to 3rd parties.

The laws that are in place create liability gaps or lacunae

CIGI also concluded that the lack of detail in the national laws that are in place creates possible liability gap situations in the event of environmental harm caused by seabed mining. This included the following situations:

- When unanticipated damage occurs (for example, plumes travel much farther than anticipated) - despite the contractor and sponsoring state complying with all obligations

- Damage occurs as a result of a third party actor who does not have sufficient funds to meet the liability (for example, a collision caused by another ship)

- Damage occurs as a result of an “act of god” (for example, a tsunami)

- An emergency disaster response is needed (for example, due to a fuel spill), but no party admits fault within the urgent time frame.

The laws in place do not adopt a strict liability approach

CIGI concluded that none of the laws in place appeared definitely to adopt a strict liability approach which focuses on responsibility for the environmental harm occurring rather than proving that it was caused intentionally. It was noted by CIGI that the use of a strict liability plus a bond from the contractor would be the most effective way for a sponsoring state to ensure adequate and prompt recompense for an injured third party, and therefore assist the sponsoring State to meet its duty under Article 235 of LOSC.

The laws in place did not provide clarity for a claimant within the sponsoring State

CIGI found that in general, there is a distinct lack of procedural clarity in national sponsorship law as to whether and how an affected party may claim within a sponsoring state for damages against a contractor. CIGI concluded that “this seems to be a startling omission.”

The laws in place do not solve the issue of jurisdiction

It is worth recalling that seabed mining in the Area will take place outside national jurisdiction, hundreds or even thousands of miles away from any coastline. In the event that environmental harm is caused by seabed mining, that harm could foreseeably affect a number of economic and other interests or rights in the ocean. However, that harm or damage will not necessarily be “caused” within the legal jurisdiction of any State, including the sponsoring State. This raises the complex legal question regarding which court located where, if anywhere, could a claimant whose interests or rights have been damaged bring a legal claim?

It is theoretically possible that the sponsoring State could via national legislation allow any claim to be brought before its jurisdiction. However, CIGI’s review of the laws that are in place found that the existing laws are largely silent as to mechanisms in place to enforce any judgment that may be made against a mining contractor, presuming domestic court procedures are even accessible. The concern is that even if the mining contractor is found liable for the damage that contractor or company may not have assets within the jurisdiction to enforce the judgment against.

In addition, CIGI noted that States including sponsoring States may have overarching immunity rules that could apply and hinder any actions too, especially because the action accrues outside the legal jurisdiction of the State. CIGI notes that this factor is unknown at this stage - as it has not been examined.

Overall Gaps in the laws that are in place

Overall, CIGI prepared a useful table that records the gaps in the legislation of sponsoring States at the present time, this revealed the following:

- Liability not expressly addressed in the national laws of:

- UK, Germany, Czech Republic, China, France

- Causes of action/standard of harm not addressed in the legislation of

- UK, Germany, Czech Republic, China, France

- Fund or bond not provided for in legislation of

- UK, Japan, Germany, Czech Republic, Belgium, China, France

- Insurance not covered in legislation of:

- UK, Japan, Germany, Singapore, China, France

- Contractor does not give indemnity to the State in legislation of:

- Czech Republic, Belgium, China, France

- No access to domestic Courts in legislation of:

- UK, Germany, Czech Republic, Belgium, Tonga, China, France, Kiribati

- Enforcement of Judgments not provided for in legislation of

- UK, Japan, Germany, Czech Republic, Belgium, Tonga, Nauru, China, France, Kiribati.

Overall conclusions based on the gaps and issues in the national laws of sponsoring States as determined by the CIGI report

The findings in the CIGI report raise significant legal risk issues for sponsoring States and point to a new industry that is not, as yet, ready to proceed in accordance with good governance and the international law framework.

LOSC has set out international law duties that are universally binding on all States and are part of customary international law. However, as things stand sponsoring States either have no legislation or have national legislation that is not fit for purpose. CIGI’s analysis shows this is not an issue that afflicts only developing States but industrialised nations too.

This failure of national legislation of the sponsoring States to meet the standard envisaged by LOSC means that seabed mining as an industry compares unfavourably with other industrial uses of the ocean like shipping. While it is true that shipping has had many years to improve its governance, this does not excuse a new industry within the ocean to commence without meeting the standard that LOSC envisaged.

It is likely that seabed mining will have as many actors who will take part in the activity including companies, contractors, sub-contractors, workers, insurers, as shipping does. But, questions like where does liability go in the event of an accident or environmental harm are largely unknown. Basic questions like whether fault required for liability or whether rules relating to exceptions, caps to liability, insurance and compensation schemes could apply, are as yet, unknown. Further other key questions remain unanswered and these include but are not limited to:

- what is the scope of claimable/compensable damages?

- Should there be significant harm before claim can be brought?

- Are pure environmental losses recoverable / can they be quantified?

- Who suffers damage if the Area is classified by LOSC as the common heritage of humankind?

- Who has standing to claim for damages (who are the claimants) - including damages to the Area and resources?

- How to avoid multiplicity of claims / what is the appropriate forum to determine claim or other dispute resolution procedure?

- How do we ensure funds are available if a claim is successful?

All of the above remind us that seabed mining is a new Industry that has never been attempted before and is likely to have unknown consequences. While mining companies provide assurances that their methods will not cause destruction or be less destructive than other proposed methods, as Dr Claire Slatter pointed out during the panel discussion, the first mining company that commences operations will open the door for others to follow.

With respect, the question that sponsoring States should be asking, amongst others, is whether they should sponsor mining operations without first ensuring that their national law has addressed all the questions to ensure that they have complied with their international legal duties pursuant to LOSC.

The CIGI report provides a list of activities or actions that sponsoring States that wish to meet their UNCLOS obligations and to limit the state’s exposure to liability arising from their sponsorship should take. This includes:

- enact a sponsorship law, which holds the contractor to compliance with the UNCLOS, the ISA regulations and contract, and sets domestic sanctions for non-compliance

- provide greater detail, and possibly more stringent standards, in national law for a contractor’s liability obligations than are currently provided by the UNCLOS

- ensure clear and accessible legal and judicial processes in-country for any claimant against a contractor, indicating causes of action and remedies available;

- consider the use of indemnities in the event of state liability; and Sponsoring State Approaches to Liability Regimes for Environmental Damage Caused by Seabed Mining

- consider requiring insurance and/or some form of financial security from the contractor on terms that enable its use to cover costs incurred by arising damage.

CIGI’s comment after reviewing the national laws that are currently in place is: “It seems surprising that so few of the current sponsoring states have taken the above steps.”

CIGI’s conclusion was that based on its review of the laws in place: ISA may not be meeting its mandate on behalf of humankind as a whole. CIGI’s report advised:

“it may be prudent for the ISA (via the Legal and Technical Commission and the Council), in considering any future contract applications, at least to enquire as to the status of sponsoring-state measures and, specifically, how the state proposes to address or meet liability for potential damage arising. Although the ISA will not want to impugn matters of state sovereignty, it is hard to see how the ISA would be meeting its mandate to act on behalf of (hu)mankind as a whole if its rules allow the permitting of exploitation under the sponsorship of, for example, a sponsoring state that has not taken basic steps necessary to ensure compliance by the contractor, does not enable civil law claims against contractors within its domestic legal system, and/or has insufficient state resources or mechanisms to meet potential third-party losses. This will be especially important in the event that the overall liability regime for seabed mining in the Area continues to be predicated on principles of state liability and access to judicial remedy via (unharmonized) domestic legal systems.”

Our conclusion: further consideration of duties under LOSC, national Laws and what is required to secure effective implementation is required

The sponsoring State’s duty under LOSC is twofold. It must enact comprehensive laws and effectively implement them. This leads to questions regarding what administrative/enforcement measures can a sponsoring State rely on. CIGI’s report comments that not much to date has been done on this - as focus has been on putting laws and regulations in place.

However, further questions for sponsoring States include determining how the individual sponsoring State will practically enforce those laws. This raises questions like what enforcement mechanisms will it use to actively supervise the seabed mining activity in the Area and how will it undertake this challenging task, bearing in mind the activity is happening 4000m plus underwater in the middle of the ocean? Further if an issue is observed how will the sponsoring State shut down the activity and what notice will it serve/how will it serve it?

This will or should lead to sponsoring States that are concerned with effective implementation questioning what sort of Regulatory body should it create to implement its regulation and what sort of personnel, equipment, technical capacity will this regulatory body require? How will the regulatory body coordinate with other State agencies, how will it monitor, control and surveil the mining activity and how, if it needs to, will it travel to the mining site?

At this point, in our respectful view, any sponsoring State that is contemplating sponsoring a mining company will want to determine exactly how much it will cost it to implement its legislation effectively and balance this against how much it will gain from the mining activity in question. After all, these duties under LOSC apply equally to developing States as they do to developed States.

It seems to us that, when these legal considerations raised by CIGI are taken into account, Fiji’s decision to postpone any seabed mining activity for a further 10 years to allow for further science to be undertaken seems sensible. It seems likely that with further scientific understanding will come further understanding of the legal risks and mechanisms that must be put in place to guard against them.

With thanks to:

USP's School of Marine Studies for hosting this informative panel discussion on this important topic, and to Dr Stuart Kininmonth for facilitating this interesting event and Mr Rufino Varea for his excellent organisation as well as to all who attended and asked questions.

.png)

Dr Greg Stone presenting arguments in favour of seabed mining

.png)

Please note: This legal bulletin is not and is not intended to be legal advice. It is published for general information purposes only.