In February 2021, the Office of the Pacific Ocean Commission (OPOC), established under the then Pacific Ocean Commissioner, Dame Meg Taylor launched an excellent “suite of Ocean reports” with a focus on ocean finance. This focus on ocean finance is well timed to assist PICs to address the major challenge of finding a way to make the protection of its ocean ecosystems both politically and economically viable.

One of the reports titled “Pacific Ocean Finance Program - Insurance” is authored by Dr. Simon Young and Jacqueline Wharton of the “global advisory, broking, and solutions company” - Willis Towers Watson. The report provides a detailed and informative discussion and explanation of the potential for a type of insurance known as “parametric insurance” to play a role in relation to adapting to the effects of climate change and to promote marine conservation.

The idea of utilising insurance products to increase resilience of coastal ecosystems is innovative but it also naturally leads to questions relating to how this type of insurance product will work and what its role could be. In this bulletin we consider how this type of insurance product could work within the legal and governance context in Fiji and the broader Pacific Island context. We also note that there are currently a number of initiatives underway in Fiji in relation to ocean insurance and sustainable financing initiatives, and these are being promoted by a number of development agencies including the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and the World Bank who are working with Fiji’s Ministry of Economy. In this bulletin we provide a brief update in relation to ADB’s project on “Partnerships for Coral Reef Finance and Insurance in Asia and the Pacific”. ADB has secured concept approval from the Global Environment Facility (GEF) for this project; which will cover Indonesia, Philippines and Solomon Islands. As this is a topic relevant to Fiji, ADB has supported[1] an initial baseline assessment to explore feasibility of including Fiji in this, or similar type of initiative. Some of the insights presented below are the result of this work.

The risks faced by Pacific Islands including Fiji

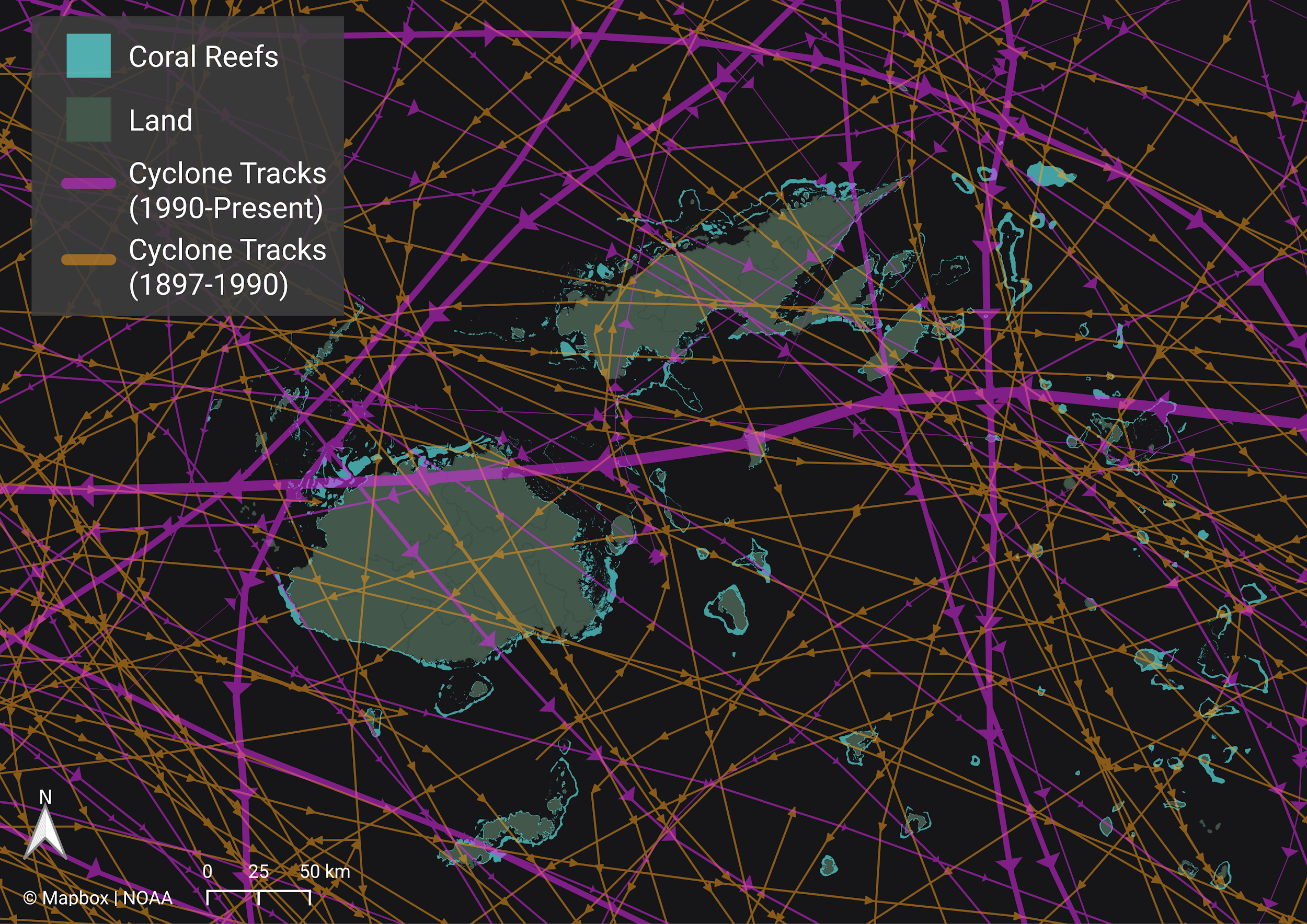

Pacific Islands are experiencing a number of negative and adverse impacts from climate change. This includes but is not limited to more frequent and powerful tropical cyclones. An example of this was TC Winston in 2016 that caused widespread and tragic devastation and remains the second most powerful storm to make landfall ever recorded.

To adapt to more frequent and intense tropical cyclones requires greater coastal resilience and marine scientists generally agree that the best way to increase that resilience is to pursue the objective of maintaining or encouraging healthy and productive marine and coastal ecosystems including coral reefs and mangroves. Pursuing this objective also makes sense for Pacific Island governments and their peoples who are highly dependent on healthy marine and coastal ecosystems including coral reefs for various reasons including economic benefits (including tourism), for food security, and for protection from the devastation of tropical cyclones both for people, property and infrastructure.

The protective role of coral reefs and healthy ecosystems

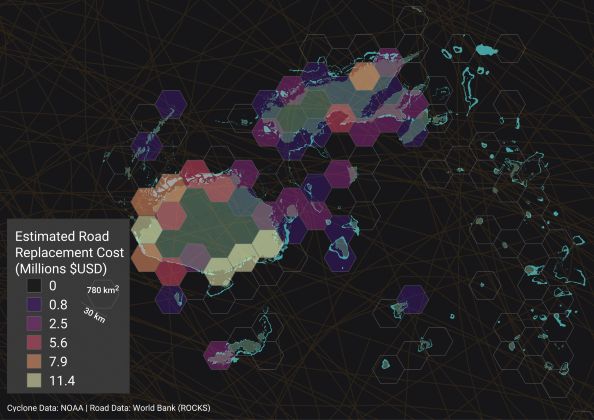

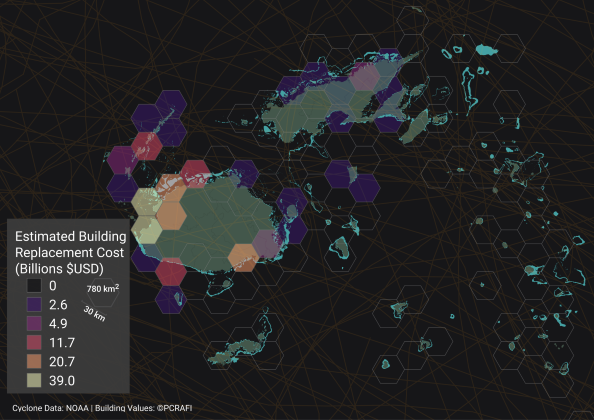

It’s quite likely that many of us haven’t given much thought to the role that healthy ecosystems, including coral reefs, play in protecting infrastructure and property on land. But there are scientific studies that demonstrate how healthy coral reefs and mangroves particularly reduce the damaging impact of storms on coastlines. Sadly, studies also show that if the coral reefs deteriorate or mangroves are removed then the protective function they provide is diminished or lost. It is nearly impossible to accurately quantify all the benefits from healthy coral reefs and mangroves, but these maps below based on data that is now out of date provide estimates for road and building replacement costs. They also demonstrate for Fiji (like many Pacific Islands) how most building and infrastructure is along the coastlines and within the areas most at risk from storms and behind coral reefs:

Major challenges includes sustainable funding

Among the many challenges, pressures and threats that Pacific Island Countries face in pursuing the objective of healthy coastal ecosystems, a pressing one - is how to find sustainable funding to promote local and community efforts to promote marine and coastal conservation. This recognises that in the Pacific, local communities are frequently recognised as the primary custodians in coastal areas vested with legal or customary rights. In addition to communities, other agencies also have an important role and/or interest in relation to conservation or sustainable management initiatives including relevant government Ministries, NGOs, academics, regional development agencies, and private sector enterprises, notably resorts. In the case of resorts, many if not most in the Pacific attract business based on offering access to enjoy marine and coastal ecosystems, and benefit from their protection from storms - meaning that they have a vested interest in keeping those ecosystems healthy.

Parametric insurance and its potential role

In Fiji, and in other Pacific Islands there are many marine conservation projects underway and this includes site based efforts to work with relevant communities and government agencies to promote more sustainable natural resource use, the adoption of rules and working with traditional and customary rights holders and harnessing traditional knowledge for more sustainable fisheries management. These projects require funding, and the challenge is to find sources of ongoing or sustainable funding to promote initiatives that work in the local context. In addition, when tropical cyclones hit they can derail existing programmes and in some cases devastate and undo what has been achieved. This is where parametric insurance may provide solutions because amongst other things if a payout is made these funds can be used by the policy holder to obtain nearly immediate funding to undertake local activities and pay local people to undertake activities around cleaning up coastal areas and other efforts to bolster the coastal and reef ecosystems.

Parametric insurance is not the same as indemnity insurance that is a more familiar type of insurance and the one that is selected for household or car insurance. The clue is in the different names.

Broadly speaking: Indemnity insurance is typically paid if an asset or a thing is insured against a particular type of damage. For indemnity insurance to be paid the damage or loss must be assessed and that takes time and the payment made may be up to the insured amount or a lesser amount that corresponds with the cost of repair/rectification.

Parametric insurance is different because it is paid out if certain parameters that can be independently verified and are out of the control of the policyholder are met. A good example would be the purchase of parametric insurance against wind speed exceeding a certain speed within a defined geographical area. In other words the policyholder would agree with an insurer that if winds went over a particular speed, for example, 100km/h in that area a payment would be made.

The reason parametric insurance could apply to a coastal ecosystem or a coral reef is because the policyholder could take out parametric insurance to cover that area and receive a payout if wind speeds exceeded the agreed wind speeds. The policyholder is not required to have an ownership interest in the area insured or the assets within that area as it is simply a contract of insurance that pays out on the parameter of wind speed in that area during the period that insurance is in place. The payout amount is also agreed in the contract of insurance and set at a fixed amount based on the parameter. In other words the payout is not assessed on the amount of damage caused by the wind speed, but just on the basis that the wind exceeded an agreed speed. Generally speaking, the wind speeds may correlate with the escalating wind speeds associated with the ascending categories of tropical cyclones. The difference is with parametric insurance the damage does not have to be assessed and this makes payouts much quicker.

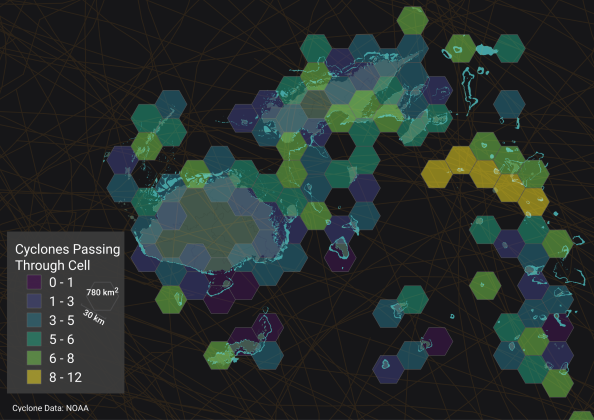

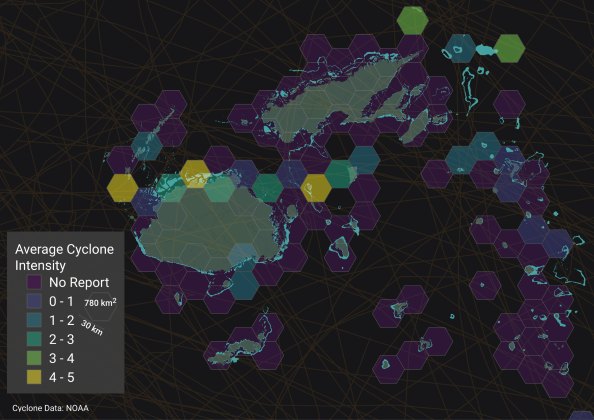

The maps below demonstrate how the defined areas could be divided into specific “cells” to enable a parametric insurance product to be purchased. This map shows Fiji the number of Tropical Cyclones that passed through each cell based on historical data accurate up to December 2020.

Practical considerations - who pays the premiums?

Although parametric insurance is a possibility within Pacific Island law and governance contexts - with the Reserve Bank of Fiji reporting it has approved one such placement of this product with an offshore insurance company in 2020 - there remain a number of questions that require careful thought.

The first is that the parametric insurance product must be purchased, and this will require a financial outlay. Based on our own enquiries, a likely annual premium could be as much as FJ$50,000 but with a payout of up to FJ$500,000 if the wind speed reached Category 5 levels, with proportionally smaller but set payments for wind speeds of Category 3 or 4 levels. However, each contract of parametric insurance will be on its own terms and conditions and any prospective purchaser of the parametric insurance would have to consider the financial and other terms carefully, as they would before purchasing any insurance product. If the insurance is placed and at no time during the year are the agreed wind speeds exceeded then there will be no payout.

The next question is who would be interested in this sort of parametric insurance product, and the answer to that question may depend on who has a vested interest in the area being insured. This is why parametric insurance may be seriously considered by private businesses like resorts that depend on coastal ecosystems for protection and business, or businesses, NGOs and communities that want to promote healthier coastal and reef ecosystems. If one of these entities has invested time and money in ongoing projects then an insurance payout following a Tropical Cyclone may provide much needed funds to provide funds to local people to meet immediate needs following a cyclone as well as undertake clean up and other operations to try to clean up or relieve pressure on coastal ecosystems following a damaging storm. This may in turn promote reef and coastal resilience that will provide more protection next time around.

Questions and Concerns

While this all sounds good in theory, there remain other questions and/or concerns that need to be considered, particularly if the parametric insurance model is contemplated to be used to build resilience to the effects of climate change, as contemplated by OPOCs/Willis Tower Watson’s paper. This is particularly important in the current economic climate and economic difficulties faced by Pacific Island Countries in the midst of a global pandemic that has effectively stopped tourism dollars.

The main questions are: how could various stakeholders come together to raise the funds to place insurance?; and how would the payouts of the insurance be governed to ensure that the money is channeled to local communities in a post cyclone scenario to ensure that the funds go towards building more resilience?

Potential benefits if the questions can be answered

If these questions can be answered, then Fiji and other Pacific Islands could receive a double benefit from any payout. This is because Fiji’s experience with Tropical Cyclones has demonstrated that what is most required to enable communities to begin their recovery is direct funding, rather than aid packages. Aid packages, although well-intentioned, frequently do not meet the immediate needs of local communities to buy what they need whether it is foodstuffs or building materials and use those funds in a way that suits their context best. Adequate funding at the right time and directly to affected communities who have planned for it could enable communities to “build back better” with a number of locally based NGOs and government Ministries providing technical guidance in this area.

The second benefit is that with adequately managed and directed funding, those communities could, in accordance with an agreed plan undertake immediate paid work to clean up and be involved in other activities related to post cyclone recovery. This would relieve fishing and other immediate pressures on the coastal environment and these activities would be paid for.

The work that is currently underway in Fiji that is being led by the Fiji government

Again, this all sounds good in theory, but each Pacific Island would have to determine how to bring the requisite agencies together including but not limited to: government Ministries, NGOs, development partners, academics and local experts to create the governance framework for the placement and management of the funds. Because the funding would be performing an essential post cyclone function in the local and public interest government must be involved in a lead role. However, because a feature of parametric insurance is the speed of payouts in post-cyclone scenarios, the insurance and payouts should not be blended with government finance as it will defeat the objective of rapid recovery. For this reason stakeholders have an option to work together in a Public Private Partnership (PPP) with a clear governance structure, and to create something like that takes time and effort.

The objective of the ADB project is: “To enable large-scale finance to increase the climate resilience of coastal businesses, communities and livelihoods in Fiji through an innovative coral reef financing and insurance model, with scope for scaling in the Pacific Region”. Below are some key findings from the ADB-supported baseline assessment:

- Fiji is at extreme risk from severe tropical cyclones;

- Fiji has some privately owned resorts that rely on pristine marine ecosystems as part of their offering, who are at risk from extreme weather events including cyclones and are already working with their local communities in accordance with those communities traditional rights that are interested in purchasing the coral reef insurance;

- Fiji has a number of key NGOs working in this area who may assist with both the operation of the governance structure for coral reef insurance and may also undertake community training for response efforts following a tropical cyclone;

- Insurance payouts placed for coral reef insurance can provide money directly to local communities after a cyclone to help with safety and resilience efforts;

- Greater understanding of the protective functions of coral reefs and coastal ecosystems as well as the ability to place insurance may also bolster preparedness for cyclones, encourage more effort to ensure coastal ecosystems and coral reefs are healthy to increase their protective function; and

- The Reserve Bank of Fiji, as Fiji’s insurance regulator has a good understanding of parametric insurance and has already approved parametric insurance products for Fiji’s private sector.

In relation to this last point, the fact that Fiji has an insurance regulator that understands parametric insurance and has approved it places Fiji ahead of many other jurisdictions in terms of coral reef insurance.

On 21 June 2021, Fiji’s Ministry of Economy brought together a group of development agencies and implementing partners including Fiji’s NGOs for a “Roundtable Discussion on Ocean Insurance”. This provided an opportunity for the various agencies to provide more information about their respective projects to identify complementarities and coordinate across various Fiji government ministries and departments.

Please note:

- This bulletin is provided for information purposes only and it is not legal advice and should not be relied on as such.

- This bulletin addresses only one option for sustainable financing of, and government involvement in relation to, the use of parametric insurance to increase direct funding for and protection of coral reefs in Fiji and other Pacific Island Countries and it is recognised that there are many other options for sustainable financing and alternative mechanisms that have merit.

- This bulletin does not reflect or purport to reflect the views of the Fiji government or any Ministry of the Fiji government.

- This bulletin does not reflect or purport to reflect the views of the ADB, World Bank, or any other agency involved in providing technical or other assistance to Fiji or other Pacific Island countries.

[1] TA-8961 REG: Strengthening Climate and Disaster Resilience of Investments in the Pacific.