Scientists have, for decades, warned us that oceans are warming, expanding, and becoming more acidic and polluted. In addition, humans are overfishing and failing to control the amount of waste material, particularly plastic, that ends up in oceans. In the face of these and other threats, Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) may be seen as a potential solution. The call for MPAs has a long history in international legal conventions, which have also expressly called for MPAs to be made consistent with the law of the sea framework after following a transparent and consultative process. This principled and process-led approach to MPAs reflects the important point that MPAs will curtail activities and potentially user rights in the ocean.

Fiji has, via government and Ministry of Fisheries leadership created several MPAs. In addition there have also been numerous community led initiatives assisted by Fiji's Locally Managed Marine Area Network (FLMMA) to establish fisheries management tools that have included no fishing zones (also known as tabu areas) within traditional fishing grounds.

Fiji’s efforts are consistent with the law of the sea framework which, at present, provides MPAs can only be created within areas of ocean where nation States have the authority to do so.

In this legal bulletin we particularly consider Fiji’s legal and governance framework, and how this may assist with the sort of transparent, open and consultative process that was envisaged in modern international legal conventions. We also briefly consider why MPAs will not be a solution, unless Fiji also adopts an integrated management approach to its oceans, which will include, but not be limited to the establishment of MPAs following due process.

From Greenpeace and illustrating the point that while MPAs/Marine Reserves may be advocated by CSOs the participatory decision-making process is the responsibility of the nation State and in Fiji this means meeting international and national decision making processes that will if followed improve the efficacy of the MPA

What and Why MPAs?

The idea of protecting areas of ocean or marine species is not new, even at an international level with international conventions dating back to the 1940s. In these early international conventions the approach tended to be to regulate a specific use of the ocean rather than the protection of marine biodiversity. For example, the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, 1982 (“LOSC”), envisages the creation of protected areas to better regulate shipping to minimise the chances and effects of pollution from shipping. Other early international conventions envisaged sanctuary areas for particular species of marine animals, but did not aim to protect whole ecosystems for biodiversity reasons.

The importance of protecting and conserving marine biodiversity for its own sake and for the benefit of human-kind arose as scientists observed and learned more about our marine environments. This rising awareness of the importance of ecosystems as a whole and conserving biodiversity was behind the Rio Earth Summit which led to 3 Conventions including the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) that has 168 State signatories.

The significance of the Rio Convention for MPAs is not just that it called for MPAs to be made with the specific aim of protecting biodiversity, but that it also called for:

- MPAs to be made after a fair, transparent and consultative process;

- MPAs should be part of a wider integrated oceans management approach based on an ecosystems based approach to the marine environment and ideally will result in a network of MPAs;

- MPAs had to respect the international law framework.

We examine these requirements and what they mean in more detail in this legal bulletin, but the thinking regarding why we should have MPAs essentially boils down to:

- Increasing Fiji’s resilience to the effects of climate change;

- Boosting Fiji's oceans ability to absorb carbon;

- Improving Fiji’s food security (particularly important in times of disaster);create a healthier environment for the benefit of all Fiji citizens; and

- Providing more economic opportunities that align with Fiji’s economy including but not limited to tourism.

What makes MPAs effective?

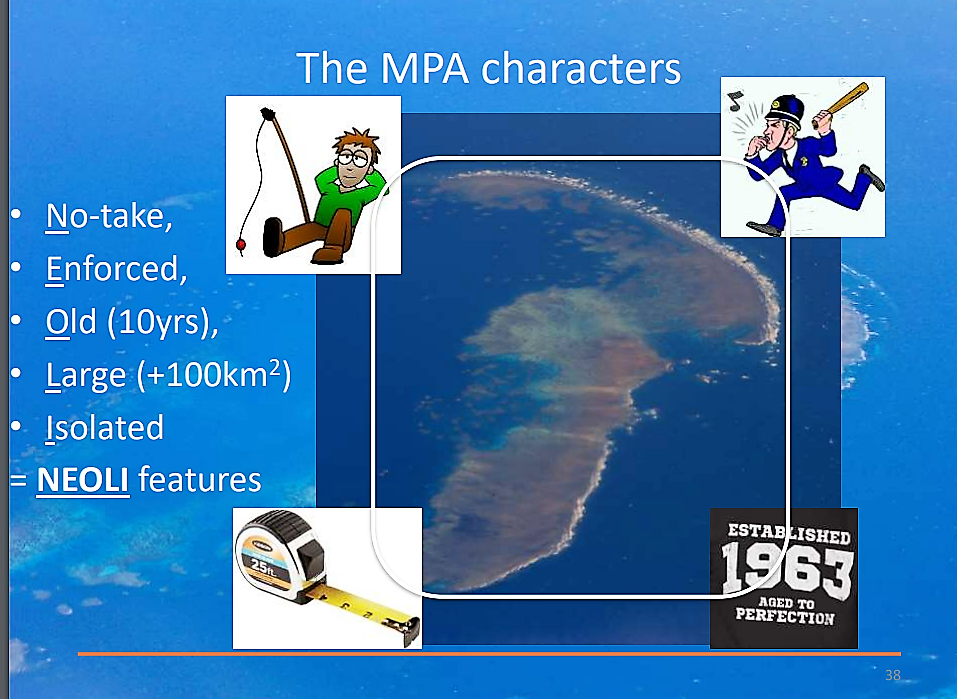

In a recent presentation at the School of Marine Studies, at the University of the South Pacific, Dr. Stuart Kininmonth, explained 5 ingredients that scientists have pinpointed makes an MPA effective[i]. This required, MPAs to be:

- No Take - meaning no extraction of resources that would include fish

- Enforced - meaning that the rules of no take had to be regulated and enforced

- Old - meaning that the MPAs that had been established for a longer time were better

- Large - meaning that the more effective MPAs covered larger areas of ocean

- Isolated - meaning that the protected zone needs to align with natural features such as an entire reef.

Dr. Kininmonth provided the following slide to illustrate this point:

While these requirements represent what marine scientists have observed, it is not always easy to guarantee these 5 ingredients (known as NEOLI) in the creation of new MPAs where they may be required.

In addition, as recognised by the Rio Convention the current international law of the sea framework does not presently allow for the establishment of effective MPAs in areas of ocean beyond national jurisdiction (the true high seas). This means that at present, MPAs can only be created by individual nation States in areas of the ocean where they have authority, meaning in their areas of ocean where they have sovereignty (internal waters, archipelagic waters, or territorial seas), or where they have sovereign rights (EEZs). This inability for areas of ocean outside national jurisdiction to be protected is one of the reasons why the United Nations is currently coordinating international efforts to make a new treaty for Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction (ABNJ).

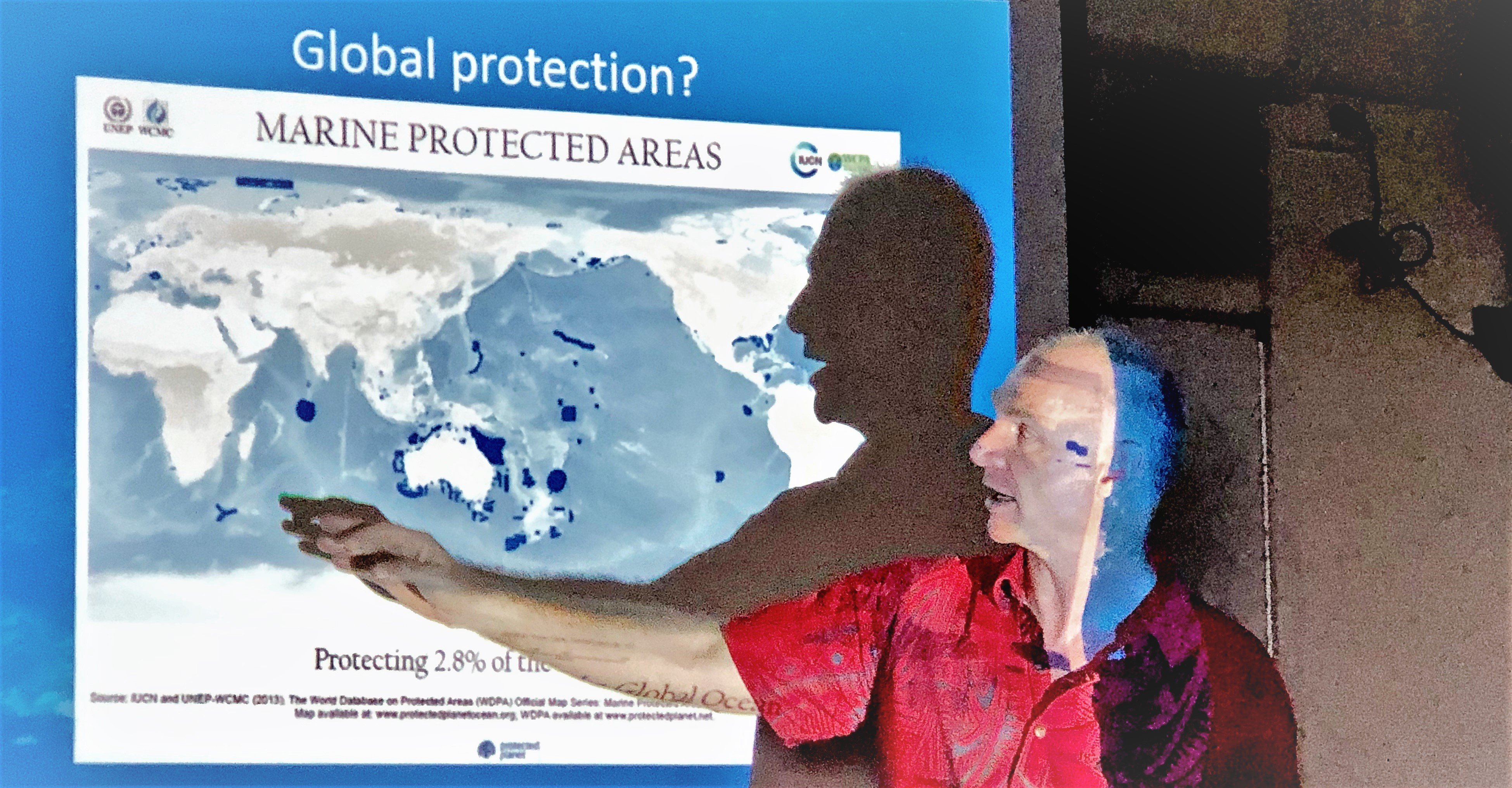

However, at the present time, even though States have the authority to create MPAs within areas of national jurisdiction or sovereign rights, including EEZs, this does not mean that effective MPAs or networks are being created there.

What are MPAs?

While there is no single universal definition of a MPA the Rio Convention and its Conference of the Parties (COP) to the Rio Convention has provided some useful guidance, including:

A geographically defined area which is designated or regulated and managed to achieve specific conservation objectives” [including marine spaces]The COP also called for networks of MPAs to be made in accordance with customary international law:

Within the context of national and regional efforts to promote integrated marine and coastal area management, networks of marine and coastal protected areas, other conservation areas, and biosphere reserves, provide useful and important management tools for different levels of conservation, management and sustainable use of marine and coastal biological diversity, and resources, consistent with customary international law.

The language used by the COP shows that MPAs have always been envisaged to be a tool for integrated oceans management, rather than a solution in themselves. This practically reflects the point that merely protecting an area of ocean from one detrimental effect (for example over-fishing) will not resolve other existential threats, like the effects of climate change, pollution, or excessive use by other industries like shipping.

Why should there be a careful, transparent, consultative and participatory process undertaken before a MPA is created?

As mentioned previously in this and other legal bulletins, the creation of MPAs will affect other users of the ocean, some of whom may have user rights. In the Fiji context this may include user rights registered to relevant groups of indigenous/iTaukei at the Yavusa level, existing commercial fishing interests, shipping interests, tourism interests or other interests and rights that should be ascertained during the MPA establishment process.

This consultative and participatory process reflects the concept of sustainable development which although not a principle of customary international law provides useful and relevant guidance for national decision making in Fiji. Principles associated or part of sustainable development include the precautionary principle, the common concern of humanity, State sovereignty (authority) with or balanced by State responsibility, the polluter pays principle and participatory and informed decision making. (Our emphasis).

The Rio Declaration went further by setting out specific principles relating to procedure, and these included public participation in decision making.

In relation to MPAs there are also good practical reasons for good process and public participation and these include, but are not limited to:

- Understanding and consultation with holders of any rights that may experience changes or constraints to those use rights due to the creation of the MPA;

- Enabling the process to provide reasons based on good science regarding why the changes are required and getting support/consent from those who participate in the process (this should make monitoring and enforcement better later); and

- Via a consultative process improving the final decision and/or particular regulations that will constitute the legal framework for the MPA.

All of the above, are consistent with Fiji’s commitments pursuant to the CBD. Amongst other things Fiji has committed to:

- As far as possible and as appropriate, establish a system of protected areas where special measures need to be taken to conserve biological diversity;

- Develop where necessary guidelines for the selection, establishment and management of protected areas or areas where special measures need to be taken to conserve biological diversity;

- Regulate or manage biological resources for the conservation of biological diversity whether within or outside protected areas, with a view to ensuring their conservation and sustainable use; and

- Promote environmentally sound and sustainable development in areas adjacent to protected areas with a view to further protection of these areas.

The principles set out above, again emphasise the importance of a consultative and transparent decision-making process, but also hint that MPAs must be established appropriately to the international legal framework - this includes, but is not limited to, LOSC. To a certain extent LOSC constrains what signatory States like Fiji can do when it comes to establishing MPAs.

How does LOSC / the framework for international law of the Sea constrain the creation of MPAs for Fiji?

The central principle of LOSC is to balance the ancient right of Freedom of the Sea against the rights or the authority of the coastal State to regulate certain areas of ocean adjacent to the coastal State. In practical terms this means that MPAs cannot generally deny rights of innocent passage/navigation across ocean areas either within its territorial sea, archipelagic waters, or Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) by ships flagged to a different State.

How to make effective MPAs in the Fiji context

Fiji is a common law jurisdiction and its fisheries legislation provides that marine reserves or MPAs can be established by Fisheries Regulations. This Regulation making power is delegated in accordance with Fiji’s sovereignty to the Honourable Minister of Fisheries and Permanent Secretary of Fisheries, depending on which area of the ocean the MPA is to be designated.

However, in accordance with common law principles, including principles of administrative law, and the rights contained in Fiji’s Constitution, 2013, as well as Fiji’s international law commitments, this does not provide the Minister of Fisheries or the Permanent Secretary of Fisheries with an unfettered discretion to create MPAs. It is respectfully suggested that the Minister of Fisheries and/or Permanent Secretary of Fisheries are empowered to exercise their discretion to create MPAs following an open transparent and consultative process that accords with Fiji's common law/administrative law system.

This is why it is often said by ocean governance experts like Yoshifumi Tanaka[ii] that the effectiveness of MPAs is dependent on a sound balance between a requirement to conserve marine biodiversity and the need for economic, social and political development of the State.

Ultimately, this means that for Fiji, effective MPAs made within its legal and governance context requires a participatory, transparent and consultative approach. This should, involve stakeholders and CSOs supporting the government’s position, but it also requires government leading this approach.

A failure to follow a consultative and participatory approach to establish MPAs creates a significant risk in the Fiji context, because, depending on where the MPA is located, its establishment could adversely affect iTaukei rights leading to sensitive and political consequences as well as a less effective MPA. In other words, a failure to consult represents a lost opportunity to do better and may erode the goodwill and participation of all involved.

Fortunately, in Fiji, the Ministry of Fisheries has good leadership and a good understanding of the Fiji context and should be well placed to provide guidance on this issue.

To be more effective MPAs should be part of an integrated management approach

As mentioned at the start of this legal bulletin, the Rio Convention envisaged, effective MPAs require more than a participatory approach to their establishment. Effective MPAs also require other uses of, and sources of pollution to be managed in an integrated way. This also confirms the observations of scientists like Dr. Kininmonth.

This does not mean that MPAs should not be created until Fiji adopts an integrated management approach, but it does mean that we are unlikely to see the efficacy of MPAs until a fully integrated management approach is taken for Fiji’s oceans that both manages and reduces the problems affecting Fiji’s oceans. Even then there will be aspects of ocean health that will be outside Fiji’s ability to manage and this requires other States to meet their international commitments to the preservation of oceans and reduction of waste by implementing their own national legislation.

Fiji is a global leader and champion for oceans, as well as for climate change and it remains an involved and participatory process to create an integrated management policy for Fiji. Such a process requires raising awareness of all Fiji citizen’s rights in Fiji’s ocean spaces and then designing these processes in accordance with Fiji’s unique common law and governance context to create this policy to guide decision-makers to reduce the threats to Fiji’s oceans and conserve its biodiversity. This is a process that those interested in the health of Fiji’s oceans may consider investing in as it moves towards an integrated and planned process.

Conclusions

While there is a call for MPAs globally, and while scientists have been explaining why protecting biodiversity is required for decades, effective MPAs require them to be part of an integrated approach to oceans to regulate all harmful activities.

To establish MPAs in the Fiji context involves understanding both the process requirements at international law level and how Fiji’s unique law and governance system has been established and expects decisions to be made that may adversely affect existing users in a participatory and transparent manner.

Fiji’s common law system supports the correct and participatory establishment of MPAs, but a good process will not just enable MPAs to achieve universal acceptance but will also provide MPAs with the best chance of being effective and based on well drafted regulations.

A failure to follow consultative and participatory processes prior to the establishment of MPAs represents a failure of governance and a missed opportunity.

Dr Stuart Kininmonth presenting to students of ocean governance at the USP's School of Marine Studies

[i] Edgar Graham, Stuart-Smith Rick, Willis Trevor, Kininmonth Stuart J, et al. (2014) Global conservation outcomes depend on marine protected areas with five key features. Nature 506:216–220

[ii] Yoshifumi Tanaka – A Dual Approach to Ocean Governance

With thanks to: Dr Stuart Kininmonth for reviewing this legal bulletin and providing permission to share information he provided to students.

Please note:

This legal bulletin is provided for general information purposes only and it is not, and should not be relied on as, legal advice.