Pollution of the oceans and marine environment is an important issue for Pacific Island Countries (PICs) because it damages natural resources, reduces the economic value of PICs' legal rights to those resources, and negatively impacts fishing communities as well as income generating activities like tourism.

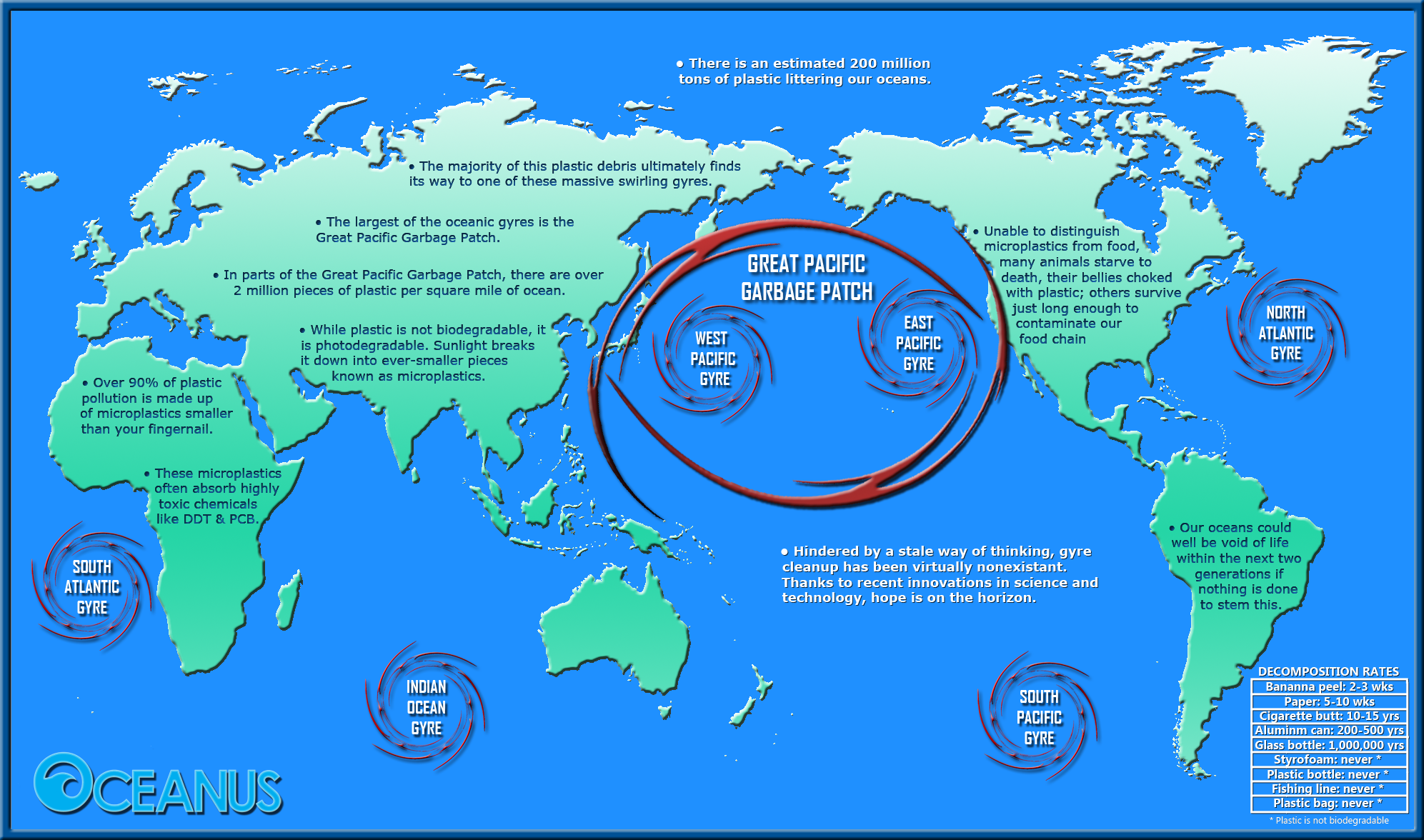

A significant challenge is that marine pollution comes from many sources and most of those sources are land based, including but not limited to, careless discard of plastics. For more information on plastic pollution in the Pacific ocean please see here

This legal bulletin examines the overall international legal framework for the protection and preservation of the marine environment set out in the the 1982 United Nations Law of the Sea Convention (LOSC) and suggests other actions that PICs, regional organisations, and CSOs may take in accordance with LOSC to address marine pollution in the Pacific ocean.

The regulation of pollution from fishing vessels in the Pacific is particularly challenging and lags behind the regulation of pollution from shipping

How LOSC works - setting the international standards

LOSC creates an overall legal framework for oceans that, amongst other things, recognises all ocean problems are interrelated. LOSC is divided into parts and Part 12 specifically addresses marine pollution with the aim of securing the cooperation of all States to protect and preserve the marine environment.

LOSC records the international obligations that all States have agreed to meet pursuant to customary international law. Article 192 of the LOSC provides that in all areas of the ocean:

States have the obligation to protect and preserve the marine environment.

Article 194(2) creates a general obligation on all States not to cause harm by pollution to ocean areas beyond their control, namely the high seas areas, and obliges States to implement their international commitments via detailed national laws that take account of the agreed international standards.

Amongst other things, LOSC also requires (Art 207) all States to "adopt laws and regulations to prevent, reduce and control pollution of the marine environment from land-based sources, including rivers, estuaries, pipelines and outfall structures, taking into account internationally agreed rules, standards and recommended practices and procedures." Further all States are obliged to work together to regulate pollution, harmonize policies and cooperate at regional levels in this regard. Article 208 extends similar requirements for seabed mining by coastal States on areas within their jurisdiction.

While pollution of the oceans is a cross-cutting issue that adversely affects all uses of the ocean, LOSC cannot in one document set out all the detailed rules and regulations that would be required to regulate every source of potential marine pollution. This explains why LOSC focuses on the general commitment and then expects States to cooperate and to meet their agreed legal obligations. This approach is also meant to be flexible and pragmatic enough to meet future challenges and threats as they arise or become known to science. This setting of agreed principles that all States agree to meet is one of the reasons that LOSC is frequently described as a “Constitution for the oceans”.

A graphic by Oceanus showing the Great Pacific Garbage Patch - in an area outside national jurisdiction (the high seas)

LOSC - a Constitution for the oceans

LOSC is also described as a “living instrument” and although LOSC has not been amended, it is intended that regimes aimed at tackling marine pollution should be created to accord with the LOSC framework. This is same approach that LOSC takes to the conservation and management of globally important fish stocks as it sets the internationally agreed standards and then requires and expects cooperation amongst all States and competent sub-regional, regional and global organisations to set and implement the detailed rules and limits of fish that may be removed from the ocean based on the best available science.

LOSC also ensures that it recognises and incorporates past and future agreed international laws relating to marine pollution provided those laws are in accordance with the principles agreed in LOSC. Article 237 of LOSC provides:

“Obligations under other conventions on the protection and preservation of the marine environment

The provisions of this Part are without prejudice to the specific obligations assumed by States under special conventions and agreements concluded previously which relate to the protection and preservation of the marine environment and to agreements which may be concluded in furtherance of the general principles set forth in this Convention.

Specific obligations assumed by States under special conventions, with respect to the protection and preservation of the marine environment, should be carried out in a manner consistent with the general principles and objectives of this Convention.”

The obvious question then is: if there is an international legal framework that obliges all States to protect and preserve the marine environment, why isn’t it working?

The short answer to this question is that in some areas it is working, and in others less so.

Photo by Justin Hofman

The context of LOSC

Freedom of navigation is the overriding principle behind the development and codification of the law of the sea. This principle recognises the importance of global trade via international shipping. It wasn’t until coastal States raised concerns about the damage to their coasts caused by catastrophic oil spills and wondered who was responsible for compensating them that marine pollution hit the international agenda. This occurred midway through the 20th century.

It was quickly realised that, unlike land based sources of pollution, coastal States lacked regulatory power or jurisdiction to control international shipping and this led to a pre-LOSC focus on the regulation of shipping due primarily to the economic concerns of the coastal State resulting from damage to its coastal areas. The first international treaties related to compensation for oil pollution damage and in 1971 the setting up of an international fund to provide compensation.

In 1982 LOSC was finalised and by that time scientific understanding of, and public concern for, the environment and oceans had increased. The LOSC, amongst other things, recognised the importance of protecting the marine environment from all sources of pollution.

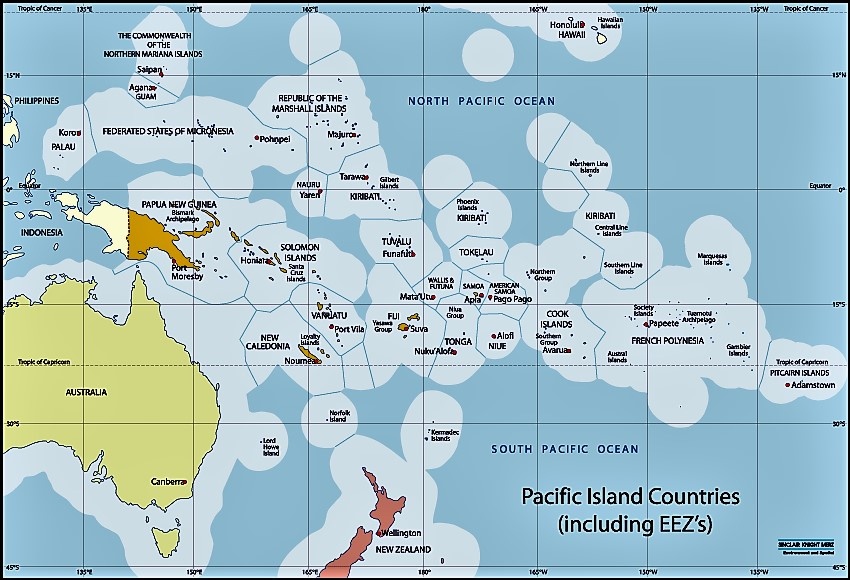

LOSC’s overall approach to the oceans and their regulation was to create new ocean zones including, but not limited to, ocean zones where coastal States have either complete sovereignty (12 nautical miles of territorial sea) or areas of ocean where they have specific legal or sovereign rights to explore, exploit, conserve and manage, Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) (up to 188 nautical miles beyond the territorial sea). To some this extension of coastal State jurisdiction in the ocean was seen as coastal State “creep” at the expense of the hallowed principle of freedom of navigation. However, the thought behind increasing coastal State jurisdiction was to boost the ability of coastal States to regulate these areas of ocean in their own interest and in the interest of the international community.

Therefore, with the arrival of LOSC coastal States enjoyed the same jurisdiction to make laws over 12 nautical miles of ocean extending directly out from their low tide marks or outer reef edges (if blessed with fringing reefs) as they had always had over their land territory. To LOSC’s drafters this meant that coastal States, in theory, had adequate law making powers to address both land based sources of pollution and marine based sources of pollution.

LOSC, with the help of scientists defined “pollution” widely to include both land based sources of pollution and other sources of marine pollution. Pollution is defined by LOSC as the “man made” introduction of any:

“Substances or energy into the marine environment, including estuaries which results or is likely to result in such deleterious effects as harm to living resources and marine life, hazards to human health, hindrance to marine activities, including fishing and other legitimate uses of the sea, impairment of quality for use of sea water and reduction of amenities.”

Further, LOSC specifically considered what vessels on the oceans could not do, and this is dumping materials overboard. While “Dumping” does not include any waste or other matter generated by the normal operation of aircraft or ships is defined to include:

“(i) Any deliberate disposal of wastes or other matter from vessels, aircraft, platforms or other man-made structures at sea and (ii) any deliberate disposal of vessels, aircraft, platforms or other man-made structures at sea.”

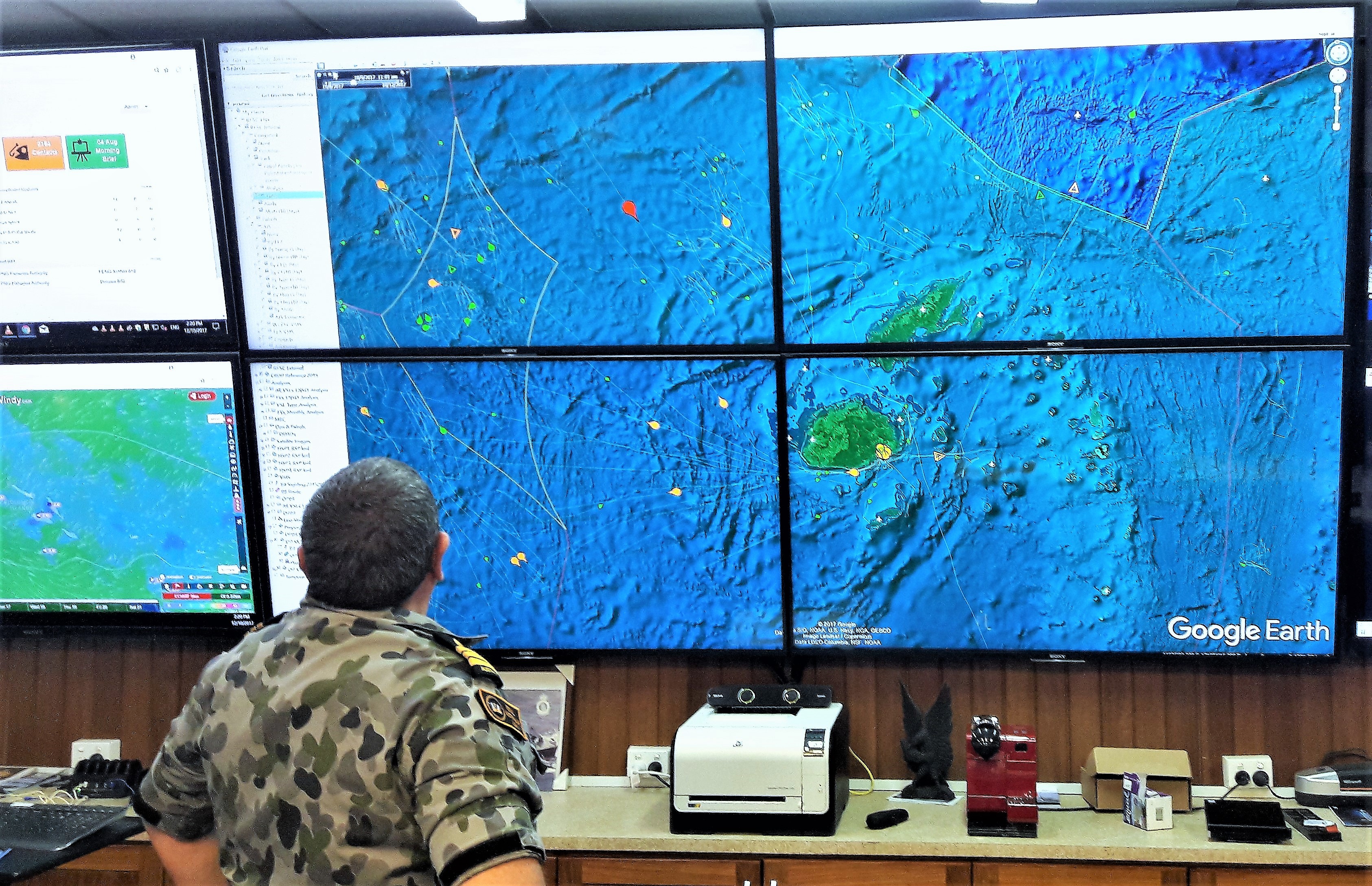

Forum Fisheries Agency HQ in Honiara, Solomon Islands, monitoring fishing activity and compliance with fishing licences issued by FFA member States to fish within their EEZs

In relation to pollution from vessels, Article 211 of LOSC provides some powers to coastal States to make and enforce "laws and regulations for the prevention, reduction and control of marine pollution from vessels", however, it is important to note that these laws must conform with and give effect to "generally accepted international rules and standards established through the competent international organisation or general diplomatic conference." Thus, LOSC recognises that although coastal States do not have territorial jurisdiction in EEZ's they have limited legislative powers to the extent appropriate to protect/regulate their exclusive sovereign rights recorded by LOSC in these ocean zones. The major challenges (particularly for PICs) are then enacting the appropriate laws and enforcing them.

The legal challenge of enforcement

LOSC recognised, amongst other things, that:

- There is no global authority to enforce standards, including pollution laws, against sovereign nation States;

- Any attempt to reach internationally agreed standards would have to be based on cooperation and agreement between separate and independent nation States;

- Following agreement at the international level, and in accordance with international law principles each nation State would have to implement national legislation to meet the international standards agreed; and

- Every nation State has different capabilities and resources to implement and enforce legislation in relation to marine pollution.

The above non-exhaustive list indicates the main challenge with regulating many uses of the oceans and this includes land-based sources of pollution. The challenge is that if each nation State does not implement and enforce adequate laws to address land or marine based sources of pollution the problem will continue to the detriment of: ocean health, PICs exclusive sovereign rights, and the interests of the international community.

Another challenge for LOSC is that in accordance with the freedom of navigation each registered vessel on all ocean areas enjoys various rights and freedoms that must not be interfered with by other States. While this area is complicated, in brief, it means that vessels on the ocean effectively have immunity from coastal State regulation with limited exceptions. LOSC attempts to resolve this challenge by requiring every vessel on the ocean to adopt the nationality of one State only and fly that State’s flag (the flag State).

In this way, LOSC vests ultimate jurisdiction for regulating and enforcing international and national legal standards over vessels to the flag State. This situation only changes when:

- the vessel is in any areas of ocean where a coastal State has sovereignty (the territorial seas, archipelagic waters or internal waters);

- the vessel berths at a port of the coastal State; or

- where the vessel is within the EEZ of the coastal State and fails to respect the coastal State's laws made in accordance with LOSC and pursuant to its exclusive sovereign rights to explore, exploit, conserve or manage its marine living resources within its EEZ.

As a result, it is only the flag State, with limited exceptions, that can take enforcement/legal proceedings against its own flagged vessels.

Generally, the coastal State will have sufficient jurisdiction to apply its national law, which may incorporate internationally agreed standards, when the foreign flagged vessel enters its territorial sea or berths at one of its ports (at this point the coastal State is a port State and has port State jurisdiction). However, LOSC ensures that flag States must be notified of any arrest of their registered vessels and while financial penalties can be applied following court process the end result is that more often than not the international community is dependent on responsible flag States to meet their obligations and take action.

Due to the operation of open registries in various nation States that are essentially commercial enterprises and provide “Flags of convenience” in return for a fee while having no real intention or capabilities to meet their responsibilities, a knotty legal problem arises that creates an obvious enforcement problem. This enforcement problem increases as vessels are able to change their flags (registering in different registrations). It is generally accepted that while coastal States are able to regulate laws pertaining to their sovereign rights, vessels determined to avoid regulation are able to do this by avoiding certain ocean areas pushing them to areas where they are aware States have less resources to regulate.

Further difficulties arise because while coastal States pursuant to LOSC are obliged to take into account international standards, ultimately, what legislation coastal States introduce is a matter left to their discretion. As a result, LOSC has not led to uniform legal standards across all jurisdictions in relation to marine pollution laws, environmental laws and other relevant laws that should regulate the uses of the oceans.

Despite these inherent challenges, LOSC does, nevertheless, require all States to collaborate to lift their own domestic standards to comply with all international standards related to marine pollution. These new agreed standards are not set out in LOSC but appear in subsequent international treaties or conventions as they are negotiated between and among States and are then hopefully enacted within national legislation.

In theory, and in practice, as our scientists discover more about how human activity adversely affects the ocean, States and appropriate sub-regional, regional and global organisations come together to agree new standards and obligations between them.

In relation to commercial shipping there has been progress because all stakeholders in that industry including the responsible shipping companies have accepted that the standards and rules set by the International Maritime Organisation (IMO) through their various Conventions set the rules for shipping. These rules apply to all ocean areas and this, therefore, includes the high seas. The rules are also detailed and intended to cover all activities relating to shipping. The IMO has been active in developing and revising treaties and keeps the 1973 International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution as modified by the protocol of 1973 (MARPOL) under constant review. As a result there are detailed and agreed rules relating to all sources of vessel pollution including oil, noxious liquid substances, harmful substances carried on the vessel, sewerage from ships, garbage and air pollution, and these standards can be enforced by the country that the ship visits.

However, when pollution incidents occur in areas beyond coastal State jurisdiction flag States may have the only enforcement jurisdiction raising again the flags of convenience/open registry enforcement issue.

While international shipping is well regulated by the IMO pursuant to MARPOL particular concerns arise regarding the regulation of international fishing and this includes pollution from fishing boats (also notably human rights and employment standards), particularly in the Pacific ocean. This pollution includes the dumping of fishing gear from fishing vessels in the Pacific that results in a host of adverse consequences for marine living resources in the Pacific. This issue has also arisen because generally speaking IMO has been focused on the regulation of international shipping and not commercial fishing.

In December 2017, the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission (WCPFC) adopted a Conservation Measure that comes into effect on 1 January 2019 that recognised the significant concerns the WCPFC has relating to a failure to regulate international standards on fishing vessels in the Western Pacific and calls for Commission Members, Cooperating non-members and Participating Territories to ratify (f they have not already done so) all annexes of MARPOL and the London Protocol. At the time of writing various PICs and the appropriate regional organisations including the Forum Fisheries Agency (FFA) are working towards the implementation of this Conservation Measure.

The Conservation Measure then sets out 12 measures that require all members of the WCPFC including PICs to regulate their fishing vessels and cooperate in a range of ways to enable the reporting of losses of fishing gear, their safe disposal and the clean up operations for existing discarded gear. For more information on the WCPFC conservation measures, please see: here

The inherent problem with the system

The LOSC framework is reactive and slow because it is dependent on developing international legal standards when the problem arises and then relies on all States cooperating. LOSC enshrines the duty on States to cooperate and Article 197 provides multiple avenues for cooperation:

“Cooperation on a global or regional basis

States shall cooperate on a global basis and, as appropriate, on a regional basis, director or through competent international organisations, in formulating and elaborating international rules, standards and recommended practices and procedures consistent with this Convention, for the protection and preservation of the marine environment, taking into account characteristic regional features.”

It is not unreasonable to suggest that the PICs that all have significant and valuable legal rights in large ocean areas will have a vested interest to ensure that their oceans are clean and healthy and utilised sustainably. However, as recognised by LOSC not all States are sufficiently resourced to meet their international obligations in their own interests. It has also been suggested that outside areas of national jurisdiction that there is little incentive for States to actively engage in cleaning up oceans. This emphasises the importance of a regional approach through all relevant regional organisations.

As things stand, the common rules that required, if they are to be found, must be in treaties, international conventions or regional conventions and then nation States must, in accordance with LOSC (Art 207-212) follow up by incorporating them into national law. This requires PICs to have sufficient intent and resources to enforce their legislation in accordance with LOSC.

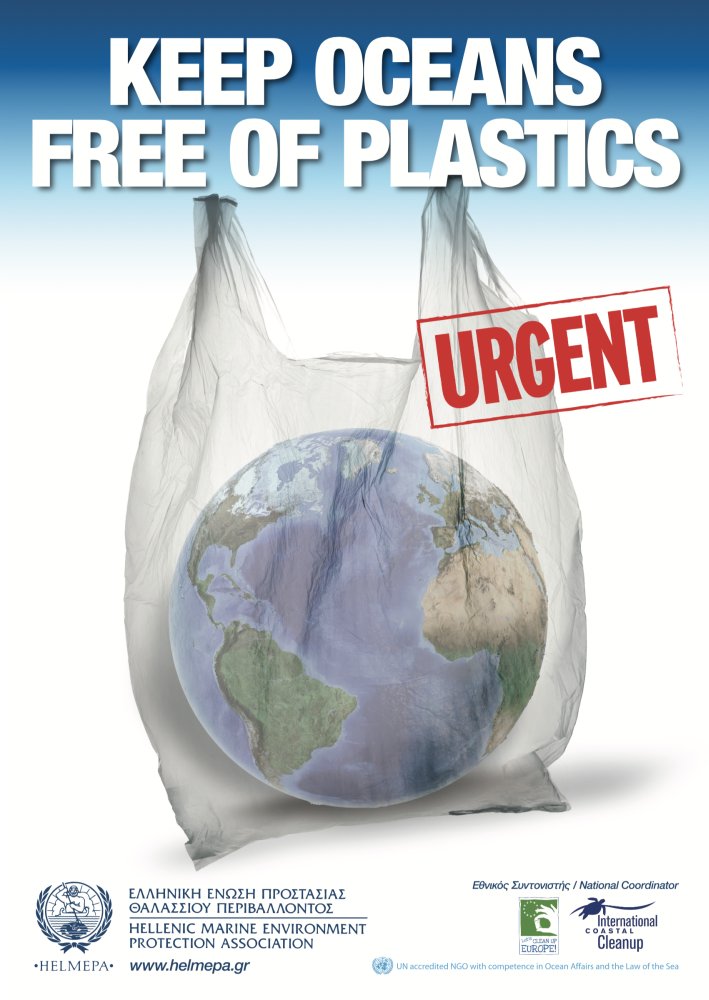

From a Greenpeace campaign highlighting the issue of marine pollution and its sources

Potential solutions

Recent and innovative legal concepts are emerging in international law that if applied within nation States provide some hope relating to national decision making to reduce sources of pollution in a more active and less reactive way.

These principles reflect or align with the duty that LOSC implicitly recognises (also recognised by the International Tribunal on the Law of the Sea) that States have a duty of due diligence and to cooperate with each other to prevent pollution in the marine environment and this includes the duty to cooperate to make contingency plans and to undertake scientific research.

The concept of due diligence in relation to environmental harm has informed subsequent international conventions or treaties and manifests in a variety of ways that includes, but is not limited to:

- the requirement for Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs) as part of a careful decision making processes before decisions that could adversely affect the environment are taken in relation to new activities that could impact the marine environment;

- duties to take account of the precautionary principle before making the decision; and

- duties on States to monitor the effects of their development decisions.

The requirement for States to exercise due diligence and undertake EIAs where appropriate should be included within appropriate national legislation and there is a good incentive for doing this. States that include the obligation within their national jurisdictions to undertake EIAs are able to demonstrate to the international community that they are taking their international duties and obligations seriously and this includes demonstrating that the State is attempting to minimise pollution across national boundaries. This recognises the point in the LOSC preamble that the problems in oceans are interrelated.

The precautionary approach to decision making suggests that when the potential effects of a decision relating to the environment is not known or are uncertain to science then a decision maker should take into account the precautionary approach and perhaps not proceed with the development in question. As a person who is standing close to a cliff edge in pitch darkness may be best advised to wait for daylight before taking their next steps, a precautionary approach may also be the most advisable way to avoid future catastrophe and permanent damage to PICs legal and economic rights.

The precautionary approach is finding its way into international treaties and conventions related to all areas of the environment including the marine environment and its approach is close to becoming an internationally agreed rule of customary international law.

Seabed mining?

Seabed mining is an important issue for the PICs because exploration is underway to determine where the valuable hydrocarbon and rare metallic resources are on seabed areas that PICs have the exclusive rights to explore and exploit (on the seabed in their territorial seas or in areas on PICs' continental shelves extending beyond their territorial sea). These areas of seabed and subsoil may contain valuable largely non-renewable resources that in the case of the rare metals are utilised in common items like phones and computers. PICs governments are likely to see an opportunity for economic benefit from licensing seabed mining activities, however, the potential negative effects on the marine environment and therefore PICs ocean/legal/economic rights are, as yet, unknown or uncertain to science.

While the seabed mining industry is, at present, in its infancy, within areas that are subject to national jurisdiction it will be incumbent on States to update their legislation in accordance with LOSC (Art. 208), as well as, exercise control and take careful decisions based on their national laws, all available science as well as the precautionary approach before approving any seabed mining activities.

States should also recall and take into account their international obligations under LOSC to “protect and preserve” their marine environments as well as take into account the value to their economies from other uses of their ocean areas including or fishing and tourism. The need for PICs to take an integrated approach to their ocean areas is evident, as is implementing careful decision making processes that take into account the views of all stakeholders and weigh as part of the decision the future value of PICs legal/economic rights in all ocean zones.

Within areas beyond national jurisdiction the seabed and its resources belong to no State but are instead vested in the International Seabed Authority (an institution created by LOSC) that holds these areas in trust for the “benefit of mankind”. How the non-renewable metallic resources in the Area are allowed to be developed and regulated is entrusted to this Authority who is expected to act in accordance with the principles of LOSC (including the duty to protect and preserve the marine environment) and international law and principles like the precautionary approach.

A map of PICs EEZs where PICs have exclusive legal rights to explore, exploit, conserve and manage

Importance of Civil Society Organisations and PICs' governments acting together

Ultimately, as can be seen from this legal bulletin how effective the international framework is to control or regulate pollution from all sources depends on a variety of factors that includes how quickly new international standards can be agreed between States.

While science plays a large part in identifying the needs for new international regulation for new sources of pollution, Civil Society Organisations (CSOs) have also played, and continue to play, an important role by identifying problems and calling for political change to address issues. For example, CSOs have drawn attention to important issues like radioactive dumping in the ocean, and Greenpeace has been credited with a general move from a permissive approach to dumping to the restrictive approach that is reflected in the LOSC and implemented by the IMO.

In the Pacific, CSOs have notably highlighted the dangers to human and ocean health from nuclear testing by Western powers. The work of CSOs may bring about change where science is still catching up and their work can speed up the adoption of regulation via political processes.

The actions of certain nations may also advance particular issues related to the marine environment, for example Australia advanced the Ballast Water Convention and while not strictly related to marine pollution, Australia has also played and continues to play a significant role in limiting Japan’s stated aim to hunt whales in the Antarctic which Japan claimed it was doing for marine scientific research purposes. Japan is currently attempting to restart commercial whaling and CSOs and the international community are currently stopping that from happening. However, Japan is now apparently threatening to withdraw from the International Whaling Commission in protest. Amongst other things, it appears that CSOs have played a valuable part in creating the concept that there is no longer a “social licence” to hunt whales. For more information on this topic see: here

The history of the development of international standards has also shown that environmental disasters can also advance the adoption of agreed rules at an international level, and as already pointed out it was catastrophic oil spills that initially led to the development of this area of law.

If the problems of plastics and other pollutants in the Pacific ocean are to be solved, CSOs and national governments of the Pacific may need to align to put more pressure on the international community. At present geopolitical interest in the Pacific region seems to have regional powers falling over themselves to assist PICs - perhaps these powers can be encouraged to do more to clean up and regulate sources of marine pollution in their own jurisdictions and regions for the benefit of PICs too?

Concluding remarks

The variety of pollution sources as well as the legal and practical challenges that the causes of marine pollution create calls for an integrated approach to the response. An integrated approach also reflects LOSC’s recognition that all oceans problems are interrelated.

Integrated in this context means ensuring that considerations of marine pollution are integrated within all ocean use regimes including fishing, biodiversity, extractive industries, shipping and even climate change when decisions are taken at the international, regional and national levels.

Reaction times to new sources of marine pollution should be quicker and better decisions relating to new developments are required. PICs’ national governments aided by CSOs can assist by calling for more action and agreement from the international community both in the Pacific and within their own jurisdictions.

The precautionary approach is starting to be applied to new treaties, and it may be sensible to expand that principle within PICs to all national decision making processes, particularly in relation to new uses of the oceans and seabed mining. After all, as is clear from the LOSC approach, there is no reason that the PICs cannot move faster than the international community to agree regional approaches together with the appropriate sub-regional, regional and global institutions in accordance with LOSC.

Peter Thomson, a Fiji diplomat and ex civil servant from Fiji, is leading a drive for cooperation and coordination to secure the implementation of the goals agreed at the UN Ocean's Conference

This legal bulletin is not, and should not be relied upon as, legal advice - it is provided for general information purposes only