At present, Tuvalu does not have a national ocean policy that unites Tuvaluans and the Government towards implementing a shared vision and aims for its ocean and resources. The need for a national ocean policy arises due to the importance of the ocean and its resources to Tuvaluans in terms of culture, food, and economy[1], the wide variety of ocean uses, and the need to protect and sustainably manage Tuvalu’s natural resources in an integrated way[2].

In this report the authors review Tuvalu’s governance context, the laws and policies that presently exist and explain why a national ocean policy is needed. The authors set out the sort of process that they think is suited to Tuvalu culture and the Tuvalu context and why they are hopeful that from this process there should emerge a way to create coordination across government and all sectors of Tuvalu society for the benefit of all Tuvaluans and Tuvalu’s ocean and the health of its resources.

The authors believe it is not enough for Tuvalu to have a well written National Ocean Policy, if it is not implemented and owned by the Tuvaluan people. This means the process to create the ocean policy must be locally driven with procedures for inclusive and respectful consultation. This is to ensure that the moralities and legitimacy of an integrated ocean policy are created along with the national ocean policy.

Part 1 - About Tuvalu

The traditional life of a Tuvaluan revolves around the ocean, and it is the ocean that connects the nine islands of Tuvalu[3] and enables families and friends to travel and meet each other.

Tuvaluan culture has been resilient and in its dances and songs, history and information is retained and passed on about how the people of Tuvalu value the ocean, and how the ocean has been an integral part of the Olaga faka Tuvalu[4].

With islands located between 5 to 10 degrees south of the equator in the middle of the Pacific ocean, Tuvalu is the fourth smallest country in the world, consisting of 9 coral islands that are scattered over a distance of 420 miles[5]. Tuvalu’s combined land area is just 26 square kilometers and the islands lie up to 4-5 meters above sea level. The soil of Tuvalu is not well suited for growing crops, and rain catchment and wells are the only sources of water as there are no rivers. This makes the ocean, and the health and sustainability of its resources integral to the health and well being of all Tuvaluans.

Tuvalu’s Gross National Income is around US$60m per annum and it is classed as a Least Developed Country with a lack of natural terrestrial resources. In addition, Tuvalu faces challenges because of its isolation, limited resources and climate change.

Despite these challenges, Tuvalu is also a large ocean State. Tuvalu’s status as a large ocean State is guaranteed by international law and recorded in the 1982 United Nations Law of the Sea Convention (UNCLOS). This means that with a total land area of 26km2, and a coastline of around 24km, Tuvalu has the exclusive and sovereign rights to harvest, conserve and manage natural resources within an Exclusive Economic Zone of 717,174km2 [link: here] which is the 38th largest EEZ globally. In total, Tuvalu has around 900,000 km2 of ocean area with internal waters, archipelagic baselines, territorial sea and the EEZ.

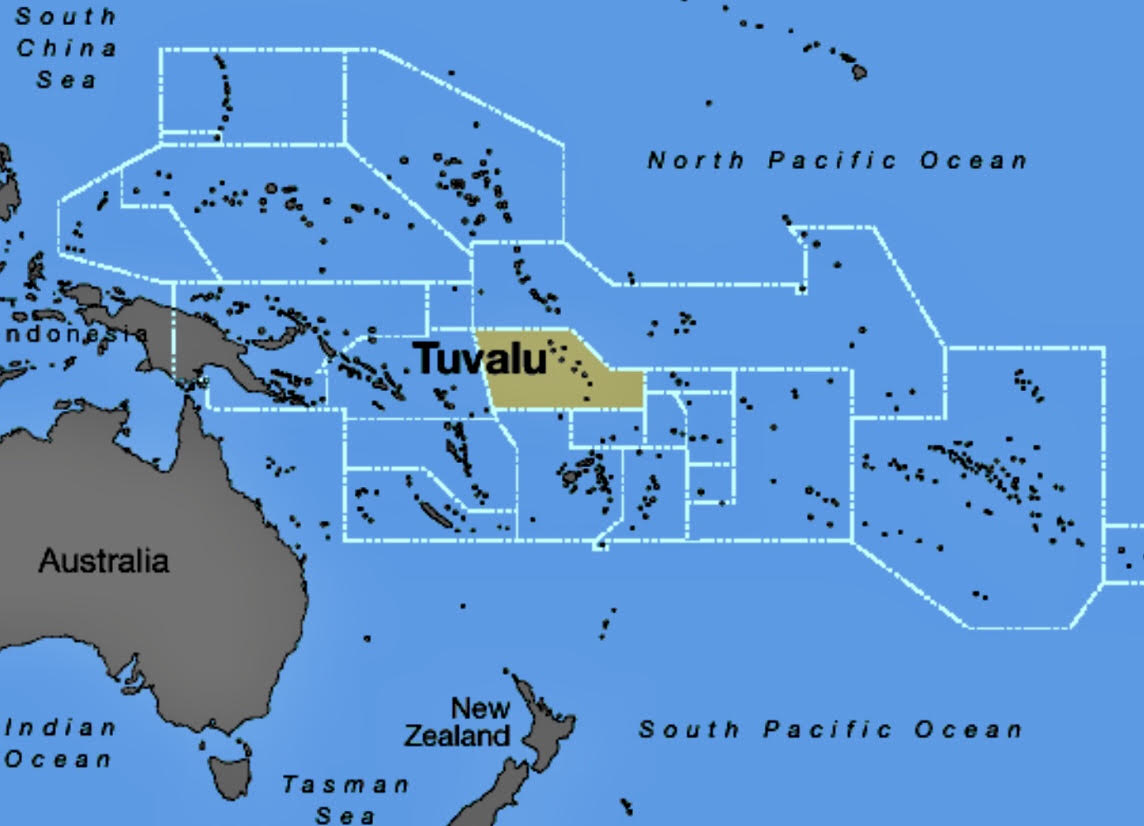

This map illustrates Tuvalu’s location and its large ocean area:

Tuvalu is a signatory to and member of the Parties to the Nauru Agreement (PNA) [link: here] , that implements the Vessel Day Scheme across the member States, and the selling of fishing licenses is the highest income-generating mechanism for the Government as this source of revenue provides a third of the Government annual spending[6].

The PNA controls 26% of the total global supply of tuna[7], and the Vessel Day Scheme is a policy that limits the number of fishing days that can be allocated to Foreign Fishing nations. Through the scheme, the members of the PNA use observers to assess the quantity and location of the fish that are caught. In the fisheries sector, observers are the eyes and ears in terms of monitoring, compliance and surveillance.

For Tuvalu, it is a matter of national importance that Tuvalu and its Pacific Island neighbours manage their fisheries resources and ecosystems sustainably.

Tuvalu is also part of the Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS) that is a coalition of small island and coastal countries. The AOSIS was established in 1990 with the recognition of the need to organise the efforts of the Small Island Developing States to address climate change and its effects.

Tuvalu’s sovereignty and sovereign rights are under direct threat from rising sea levels, and in 2017 the Tuvalu Coastal Adaptation Strategy targeted the protection of the coastlines. The primary areas of concern include: Funafuti, Nanumea, and Nanumanga that have high density of populations. The Tuvalu coastal Adaptation Strategy is essential because it incorporates a systematic and comprehensive framework to address both coastal inundation and erosion.

Tuvalu has made several obligations at national, regional and international levels in order to well manage the marine environment. In the context of the Pacific, there is an overabundance of managing policies and agreements which was designed for sustainable ocean development and conservation. However, Tuvalu on its own does not have any National Ocean Policy to manage and conserve its ocean, apart from regional and international agreement and laws. Thus, Tuvalu has national legislation and laws which were designed in line with the concept of executing what has been stated in the Law of the Sea.

In terms of the most significant use of Tuvalu’s ocean, fishing - offshore fishing within Tuvalu’s EEZ is virtually all conducted by foreign fishing vessels under licence from Tuvalu, and domestic small scale fishing takes place closer to shore and within Tuvalu’s territorial sea.

Part 2 - Law and governance in Tuvalu

Tuvalu is a common law jurisdiction and has the Constitution of Tuvalu (Cap 1.02) that includes human and constitutional rights to its citizens.

Tradition and culture continue to play an influential role in Tuvalu, and the law recognises the role of traditional decision-making and localised governance. For example the Falekaupule Act, 1997 (revised in 2000), empowers Kaupule (island councils) to regulate fishing or hunting in line with the Fisheries Act and/or Wildlife Conservation Act. Another example is the Funafuti Conservation Area Order revised in February, 2020 (originally 1999) which is promulgated under the Conservation Areas Act of 1999. This has led to the creation of a Stewardship Plan for Funafuti that is based on a “whole-Atoll approach” recognising the role of people and healthy eco-systems in fisheries. Makolo et al in 2017, explain:

“Focusing on smart use of the already established Funafuti Conservation Area (FCA), avoiding the introduction of too many complex rules and seeking to preserve and enhance livelihoods and food and nutrition security for Tuvaluans living in Funafuti. The Funafuti Reef Fish Stewardship Plan was implemented to ensure reef fisheries recover to more productive levels. The most difficult aspect of the plan to understand is that a reduction in fishing pressure will within a short time (a few years) lead to greater productivity with less future fishing effort”

In terms of the activity of fishing, Tuvalu has comprehensive fisheries laws and the Department of Fisheries which is part of the Ministry of Fisheries and Trade regulates fishing pursuant to the Marine Resources Act (48.20). Fisheries law aims to conserve, manage and regulate fisheries via licences. Fisheries licences may be subject to conditions including the terms of access for foreign fishing vessels. A common condition supported by the legislation and Access Agreements for Purse seine Tuvalu licenced vessels is the requirement for a Tuvaluan Observer (s.30(3)(a) MRA) to monitor the fishing activity for compliance with the licence and to ensure compliance by Tuvalu with its obligations under the Fish Stocks Agreement, the Western and Central Pacific Tuna Convention or any other applicable international instruments. Tuvalu’s fisheries laws also provide wide powers for its Authorised fisheries Officers to regulate compliance and there are also serious offences for failure to comply with the law.

Tuvalu has recently introduced updated and comprehensive employment legislation and has developed the Tuvalu National Policy and legislation (2020) on Crewing Onboard Fishing Vessels “to promote a sustainable seafaring industry in Tuvalu in order to contribute effectively to the social and economic growth of the country”. This Policy will aim to improve working conditions on fishing vessels.

Other relevant legislation, and policy includes but is not limited to:

- Marine Resources Act, 2006 (as amended)

- Fisheries (VMS) Regulations (2000)

- Conservation and Management Measures (PNA 3IA) Regulations (2009)

- Maritime Zone Act (2012), including:

- Declaration of Archipelagic Baseline (2012)

- Declaration of Territorial Sea Baseline (2012)

- Declaration of the Outer Limits of the Territorial Sea (2012)

- Declaration of the Outer Limits of the Exclusive Economic Zone (2012)

- Declaration of the Outer Limits of the Continental Shelf (2012)

- Falekaupule Act (1997)

- Conservation Areas Act (1999)

- Funafuti Conservation Area Order (1999) (revised 2020)

Tuvalu’s government has implemented 3 National Sustainable Plans called Te Kakeega (I) (II) and (III) which literally translates “The Ladder” which resonates the country’s need to surmount any obstacles to achieve its development objectives.

Te Kakeega III had new strategic areas added that reflect the priorities of the current Government and this included the strategic thematic area of ocean and seas to ensure that Tuvalu increases its efforts to conserve, protect, manage and sustainably use ocean areas, and it implements strategies on coastal zone management and ecosystems based management. This also aligns with SDG 14.

There are several different Ministries that have some responsibility for oceans or ocean related activities being:

- The Ministry of Fisheries and Trade that looks after fisheries, maritime boundaries and oceans

- The Ministry of Foreign Affairs - responsible for marine environment, climate change, sea patrols and international ocean forums

- Ministry of Transport, Energy and Tourism - covers shipping, ports and marine cables

- Ministry of Environment

- Office of the Prime Minister –the department of lands which covers ocean minerals.

Although there has been a renewed focus on the ocean, there is no ocean policy in place and questions remain as to which Ministry would take responsibility and lead the development of the national ocean policy.

Whether the Ministry of Fisheries has capacity to develop and implement the ocean policy is unclear given the cross cutting issues and it may be that other Ministries may be more suitable to run a coordinated process to create and implement a national oceans policy.

Part 3 - Why a National Ocean Policy is necessary

For centuries Tuvalu people fished without any serious deleterious effect on their fish stocks. But now things are different and the threats to the ocean and its resources are well known and include but are not limited to: pollution including from land and ocean use, overfishing, destructive human practices, and climate change. Good ocean governance via the implementation of integrated management approaches to the ocean will reduce the threats to the ocean and mitigate future consequences. Each year the amount of fishing fleets entering Tuvalu’s EEZ seems to increase.

A good ocean policy provides a framework for sustainable development, management and conservation of oceans resources and their habitats. It provides guiding principles and collaborative action for individuals in order to promote responsible stewardship of the large oceans for national, regional and international benefit[8]. It also guides regional coordination, integration and collaboration on ocean issues to meet the international goals of improving ocean governance.

A National Ocean Policy can help to establish laws that will be adhered to and a particular priority of national importance will be to ensure fishing is undertaken sustainably in the EEZ, as decreasing fish stock is a major threat to Tuvalu and other Pacific Large Ocean States. Hence formulating a national ocean policy may be the only way in which can minimize the over-exploitation of marine resources within the Tuvalu EEZ to improve fisheries and more general ocean governance by better regulating activities that may be harmful to Tuvalu’s ocean and natural resources.

Ocean governance is the integrated conduct of the policy, actions and affairs regarding the world's oceans to protect ocean environment, sustainable use of coastal and marine resources as well as to conserve its biodiversity. The most important international law, which directly influences the governance of marine resources in the Pacific Oceans is the ‘Law of the Sea’ or UNCLOS. Whilst the most important regional conventions that directly influence the development and management of oceanic fisheries resources in PICs are the FFA, PNA & WCPFC. FFA together with SPC are the two main regional institutions which play a major role in development and management of fisheries, by providing technical and policy advice and guidance on fisheries issues. At the political level, the Parliament and Government through the Cabinet are the supreme authority responsible for making laws and policies regarding the development and management of marine resources. The Cabinet decisions are based on technical advice conveyed to it by the Minister responsible for fisheries.

Annala, 2007 explains the importance of governance for fisheries:

“Governance plays an important role in conservation of fish according to a particular nation’s rules and regulation to conserve the fishes. Governance can be explained, as it’s a whole of public as well as private interaction taken to solve societal problems and as per create a solution accordingly, it includes the formulation and application of different principles which support those interaction and care for institutions that enable them. Different countries have different policy for ocean fishery to conserve the fishes, which will help to maintain the ecosystem in a proper manner”

However, to work and make the changes that Tuvalu needs and for the National Ocean Policy to be effective the most important thing for us, as Tuvaluans, is to create procedures and moralities to ensure coordination across all sectors of Tuvalu’s government and economy and to facilitate cooperation among interested parties, and eventually to sustain a healthy Ocean through integrating management approaches.

As mentioned Tuvalu relies heavily on marine resources which flow naturally through the Ocean and depend on the accountable management of numerous stakeholders, however, the main objective of the national ocean policy is to harmonize and promote a unified and supportive national approach in order to manage the Tuvalu EEZ in a way which promotes security, sustainability and ensures prosperity for Tuvaluans.

The idea is that when implemented the National Ocean Policy will control, prevent, improve and restore the Ocean ecosystem, climate services and biodiversity in which these benefits may equitably be shared through the sustainable management of Tuvalu Ocean, including its internal waters, territorial seas and the EEZ.

This means the most important part of creating, establishing and formulating a policy is consulting with relevant stakeholders to gather and collect the vital information which is very important in designing a national ocean policy in Tuvalu. This leads us to humbly suggest that the process required is in line with UNCLOS and other treaties and agreements that encourage cooperation and peaceful, sustainable and equitable use of the ocean and its resources. We also think this process accords with Tuvalu’s governance context that if followed will see the National Ocean Policy emerge as well as the lead agency or agencies that will implement it across Government.

Part 4 - A good process is necessary to create the National Ocean Policy

To create a National Ocean Policy for Tuvalu, it is essential to obtain accurate ideas and information from stakeholders including but not limited to:

- Communities - coastal, indigenous and local communities

- Landowners

- Falekaupule

- Kaupule

- Tuvalu Fisheries Department (TFD)

- Other relevant departments/Ministries from the government

- Fishers themselves

- regional and international stakeholders

- Schools/Secondary schools

- Youths

- Community leaders

- Religious leaders

- Women’s groups

- Journalists

- NGOs

This process must ensure that no one is left out in the creation and establishment of the national ocean policy.

The first objective is to convey all the information regarding why a national ocean policy is required. This should aim to ensure that the people of Tuvalu see the need for such an ocean policy. This could include:

- Current issues or concerns with fisheries

- Other environmental issues of concern that could be impacting the lives or resources of Tuvaluans including marine pollution.

The start should be to conduct public awareness of the issues and this should also cover how ocean use is being regulated at the moment, and particularly fishing. This should cover monitoring, and how various management approaches from licences to moratorium or other closures are working. Points that may arise could include: better boat/vessel identification, fish size limits, fishing gear restriction, controlling pollution and habitat damage, utilizing by-catch from transshipment vessels and creating or strengthening existing rules.

Once the consultation is complete and information has been gathered, and after ensuring the precautionary approach is taken into account, the government or leading Ministry may draft a concept paper that would detail the issues that the National Ocean Policy must address and the measures that could be implemented by the National Ocean Policy in order to resolve them while ensuring that these will align with the National Sustainability plans for Tuvalu.

This concept paper should state the objectives, guidelines and outcome of the consultations and include all other relevant information like the time, process and estimated budget/costs to create the National Ocean Policy.

The Concept paper should be submitted to Cabinet/government for its consideration and if a budget is approved then this may enable public funds to be used for the formulation of the National Ocean Policy.

The next stage will be to start the consultations with relevant stakeholders and raise further awareness of the National Ocean Policy. This should include:

- Radio/TV shows

- Panel Discussions

- Face to face consultation with all stakeholders in public meetings.

The purpose of this stage is to engage all groups of people who use the ocean and get their views. Once this stage is complete the drafting of the National Ocean Policy should commence based on all the issues raised and discussions that have taken place. Knowledge and experience from neighbouring countries like Kiribati, Nauru, Tokelau and Fiji may be drawn upon as they may have existing ocean policies. From this stage the first draft of Tuvalu’s National Ocean Policy will emerge.

The next stage will be for the first draft of Tuvalu’s National Ocean Policy to be vetted by the Attorney General and then circulated within all Ministries and selected stakeholders. This will lead to a second draft and this will then be submitted to Tuvalu’s Development Coordination Committee (DCC) which is made up of the Permanent Secretaries of the Government including the Director of Planning and Budget and the Director of Evaluation and Monitoring Unit. At this stage, and if approved, Tuvalu’s National Ocean Policy will be tabled to Cabinet for final approval.

The time that it will take to develop the National Ocean Policy for Tuvalu will be 6-12 months but could be longer as there will have to be consultation across the 9 main islands and this will require travelling and logistical arrangements.

Once completed, the National Ocean Policy will require ongoing monitoring and it should be updated on a regular basis - every 4-5 years or so.

A good process will ensure that the policy is adopted within Tuvalu by Tuvaluans and it will not be from somewhere else. This means that the National Ocean Policy will be suitable to the life and people of Tuvalu. Adopting a policy from somewhere else will mean it will be hard to understand and hard to implement. To enable the creation of a policy that is efficient and relevant to the context of the need and use of the ocean to the Tuvaluan people, it is of the utmost importance that the government or relevant Ministry should value the views and concerns of society as collective thoughts are valuable.

Part 5 - Constraints and issues

Tuvalu is an isolated and a least developed State. The main constraints will be to ensure that the consultation process is full and thorough and this will require travel and logistical arrangements across the 9 islands. In order to resolve this issue, Tuvalu will have to seek assistance from donor organisations that are prepared to support the development of Tuvalu’s National Ocean Policy led by Tuvaluans. This should ensure that technical assistance in drafting strictly follows the process and discussions that emerge from the consultation within Tuvalu.

There could also be issues in determining the lead agency for the development of the National Ocean Policy and which government agency should be responsible for its implementation. To resolve this issue, it may be necessary to ensure that during the consultation and drafting stage, clear responsibilities of each Ministry/agency is defined but also to ensure that all Ministries/agencies adopt and support the aims and vision of the National Ocean Policy.

Conclusions/Recommendations

Tuvalu’s national ocean policy may provide the necessary guidance for Tuvaluans to take the next steps towards good oceans governance. But the policy should be developed in line with the stages/process set out in this report to ensure it is workable. Once in place the policy needs to be monitored by the Government to ensure it is working for all Tuvaluans.

We consider that a National Ocean Policy can be developed in a way that ensures the maintenance, restoration and protection of the general health of Tuvalu’s ocean. The sustainability of the ocean and its ecosystems are essential for Tuvaluans and the rest of the world. This is because the policy should set out how all uses of the Tuvalu’s oceans and resources will be regulated to meet the vision and aims of the National Ocean Policy and provide a way to curb the adverse effects on the ocean from human activities and behaviour. The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals call for concerted and collaborative efforts to preserve the ocean[9].

The main points about the National Ocean Policy are that it should be:

- Locally driven by Tuvaluans

- Linked with existing law and governance framework - not another policy drafted by a technical agency

- Promote good decision-making process by setting goals and realistic locally driven time frame to get there

- Bring everyone along with us.

But there are constraints and Tuvalu would require support from development partners to enable the formulation of the policy. Tuvalu’s traditional donors may provide assistance, but our view is that Tuvalu must be careful to ensure that the process is led by Tuvaluans and not external experts or consultants.

In our view the ocean is life to the people of Tuvalu, and there is a high chance that all people will be responsible for taking care of the ocean resources. The views of the Tuvaluans matter because of the importance of the ocean and any dire consequences from a failure to look after it and its resources will affect all people. Tuvaluans appreciate all the benefits that they have reaped from the ocean and will play their part in ensuring that the ocean remains vibrant and alive for future generations.

End Notes:

[1] During a 2017 UN Oceans Conference plenary session held in New York, Tuvalu’s Prime Minister, Enele Sosene Sopoaga pointed out that 40% of Tuvalu’s annual National Budget is derived from the ocean (Sopoaga, 2017). The other major sources of revenue are overseas remittances, small scale copra exports and revenue generated by the government from the sale of the dotTV domain name and the sale of postage stamps along with the proceeds of the Tuvalu Trust Fund - The GNI for Tuvalu’s economy is US$63m per annum - link here

[2] Dempsy, 2002

[3] Tuvalu’s islands are: Nanumea, Nanumanga, Nui, Niutao, Nukufetau, Niulakita, Vaitupu, Funafuti and Nukulaelae and these are a mix of coral reef islands or atolls.

[4] Tuvaluan way of life passed from generation to generation by word of mouth.

[5] Macdonald, 2020

[6] Government of Tuvalu, 2020

[7] Ceccarelli, 2019

[8] SPC, 2005

[9] Ceccarelli, 2019

About the authors:

Scott Pelesala - is a Tuvalu civil servant and Fisheries Licensing Officer. Scott is currently undertaking studies at the University of The South Pacific to obtain a Bachelor of Arts in Marine Management. Growing up in an environment surrounded by the Ocean has driven Scott’s interest to work for better ocean health and governance at national and regional level. Scott considers that it is important for Pacific Island Countries to collaborate to promote a balanced environment and that all Tuvaluans should ensure that their ocean is a healthy Ocean so that it can continue to shape and inspire the culture and identity of Tuvaluans in the longer term. Upon completion of his degree in Marine Management Scott plans to return to Tuvalu to continue working as a law enforcement officer to protect the Ocean, and the sustainable use and management of all marine organisms.

Maani Petaia - is an experienced Fisheries Officer specialising in Coastal Fisheries Management. Maani credits his direct involvement at the Tuvalu Fisheries Department at this level for the opportunity to obtain fisheries work experience, practical knowledge and skills. Maani is currently studying at the University of the South Pacific pursuing his program (Bachelor in Marine Resource Management) and is a third year student. Maani’s ambition to achieve his recognized tertiary qualification to enhance his knowledge and understanding of sustainable marine resource development and management. Maani is committed to contributing significantly to the sustainable development and management of marine resources in Tuvalu and the Pacific region. Maani was fortunate to have served the Tuvalu Fisheries Department for ten years, and hopes to continue serving the Government and people of Tuvalu upon completion of his studies.

Onosai Takataka - is an experienced Observer Coordinator for the Government of Tuvalu. Onosai is responsible for the coordination of Observer activities including placing and providing the information needed by observers on board fishing vessels to make sure that they are safe and comply with regional arrangements. At the present time, Onosai is a third year student, pursuing a Bachelor of Marine Management at the University of the South Pacific. It is Onosai’s view that the ocean is life to the people of Tuvalu and he intends to combine the knowledge he has acquired during his degree program with his passion and commitment to a healthy ocean in his future work at the fisheries department and upon his return to Tuvalu. Onosai is committed to contributing in any way possible in nurturing the Ocean and its resources. Onosai’s belief is that a healthy Ocean is best for Tuvalu and to achieve this it is essential for the Pacific Communities to work together to promote good stewardship of the Ocean. He says:

“The Ocean gave life to me, it is time to give back to the Ocean”.