The movement of migrant workers isn’t so much a global hot topic as a burning one. At the LAWASIA Employment Law Forum, 25-26 January, 2019, the key note presentations aimed to address Migrant Labour Issues: The Rights of Migrant Workers and the Obligations of Employers. An objective of this session was to share among delegates how migrant labour is regulated and what challenges are experienced in various Asia Pacific jurisdictions.

This commercial law update is based on the key note presentation provided to the conference to provide an overview of how migrant labour is regulated in Fiji and the Pacific. Due to time constraints for the key note presentations this update expands on some of the themes discussed during the key note presentation at the conference.

For more information on LAWASIA please see here

This was a campaign image from part of the Vote Leave campaign Brexit Referendum in June 2016. It was reported to the police prior to the Referendum for inciting racial hatred and it is actually a photo of migrants crossing the Croatia/Slovenia border. Regardless of its aim and inaccuracies images like this used for political end demonstrate the importance of good regulation and transparent information.

Challenges

Fiji and other Pacific Island jurisdictions face various challenges in the regulation of migrant labour, and these challenges are common to other regulatory areas. First, we have the challenge of limited resources, and secondly each Pacific Island is a separate legal jurisdiction with different laws and regulations.

International framework

In terms of migrant labour and the rights and freedoms of migrant workers and their families there is no uniformity of laws across Pacific Island jurisdictions. This is partly due to the fact that no Pacific Island jurisdiction has ratified the International Convention on the Protection of all Migrant Workers and their families (International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers) (Convention Text). [Please note, since this commercial update was posted, Fiji's Parliament voted on 16 May 2019 to ratify the Convention].

The International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers ("Convention") was adopted in 1990, and it entered into force in 2003 when twenty States ratified the Convention meeting the ratifying threshold. At the time of writing, fifty-four States in total have signed the Convention that is a comprehensive treaty protecting human rights and freedoms and setting minimum standards for the protection of migrant workers and their families. This includes respect for human rights, freedom of thought and religion, equality of treatment and commitment to stopping illegal and nefarious activities designed to encourage illegal migration.

The Convention provides that a "migrant" is a person engaged or remunerated in a State where the migrant is not a national, and this may include a foreign worker or an expatriate. Seasonal workers are also defined as a category of migrant workers although foreign investors and those who work for their own States in another jurisdiction are not migrant workers.

The majority of States that have adopted the Convention are those that tend to be the origin State for most migrant workers - i.e. the "giving" rather than the "receiving" jurisdictions for migrant workers. While, no Western States or States that receive the largest number of migrant workers have ratified the Convention, the Convention sets a moral standard that States should consider when looking at their own national employment legislation.

However, for the time being, the majority of migrant workers who travel to and work in jurisdictions that have not ratified the Convention must rely solely on the national laws of their host State, which may vary dramatically between jurisdictions, including in the Pacific.

Fiji and Pacific context

During the key note presentations the Conference heard from Attorney-At-Law, Mr. John Dong (Baohua Law Firm john.dong@baohualaw.com) that China employs an estimated 300 million migrant workers. Fiji and the Pacific's relatively small land size and isolation means we do not have those kinds of numbers, but various Pacific Island States are aware that China also supplies migrant workers to the Pacific and this has increased in recent years as the speed of development/investment from China picks up.

While the Pacific has its own history of migration most notably due to colonialism in the 19th Century, which brought more people from various places to the South Pacific, with effects that are still being felt at a political level, the Pacific at the beginning of the 21st century finds it is in a new "geo-political hotspot". This is evidenced by the various efforts of development partners like Australia, New Zealand, China, the UK and the US to assist Fiji and the Pacific with various development projects. In Fiji and elsewhere we are seeing more development or development is speeding up with increased cars, roads, and construction projects being the most obvious indicators.

Further challenges that we are facing include:

- much of the inward migration is handled at a government to government level with Memorandums of Understanding ("MOUs") signed between governments that will set the terms and conditions for inward migration of workers but won't necessarily be publicly available; and

- Climate Change - while it is a global issue - for Fiji and the Pacific it is likely to increase pressure for good regulation of migrants due to increased migration within/around the Pacific. Fiji has already publicly stated that it is ready and willing to assist climate change refugees from the Pacific.

Economic effects of migration for Fiji

The United Nations provides good info-graphics and other information relating to the positive economic effects of migration. Below is an example, for more information please see here

This information intends to demonstrate the positive side of labour migration by making the economic argument for migration. The difference from the Vote Leave campaign imagery from the UK is that the UN is trying to appeal to heads rather than emotions. There are reasons why labour migration is good for richer countries as economic opportunities are met, but it is also good for developing economies.

Fiji bears testament to this as personal foreign remittances (mostly money sent back to Fiji from workers overseas) have grown each year to the point where in 2018 - foreign remittances exceeded F$0.5bn for the first time making foreign remittances Fiji's highest foreign exchange earner surpassing even tourism.

Fiji and the Pacific are origin countries for migrant labour

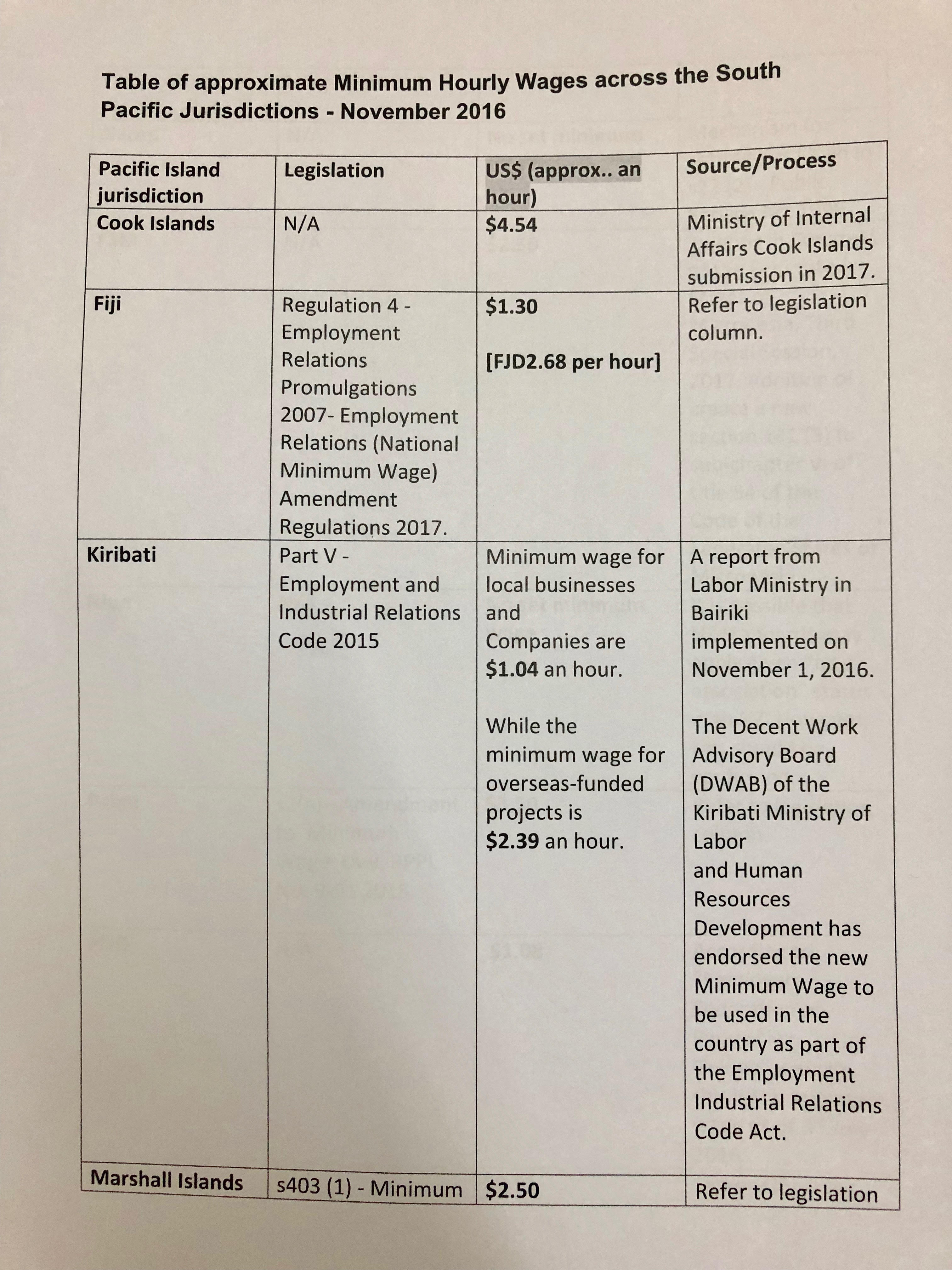

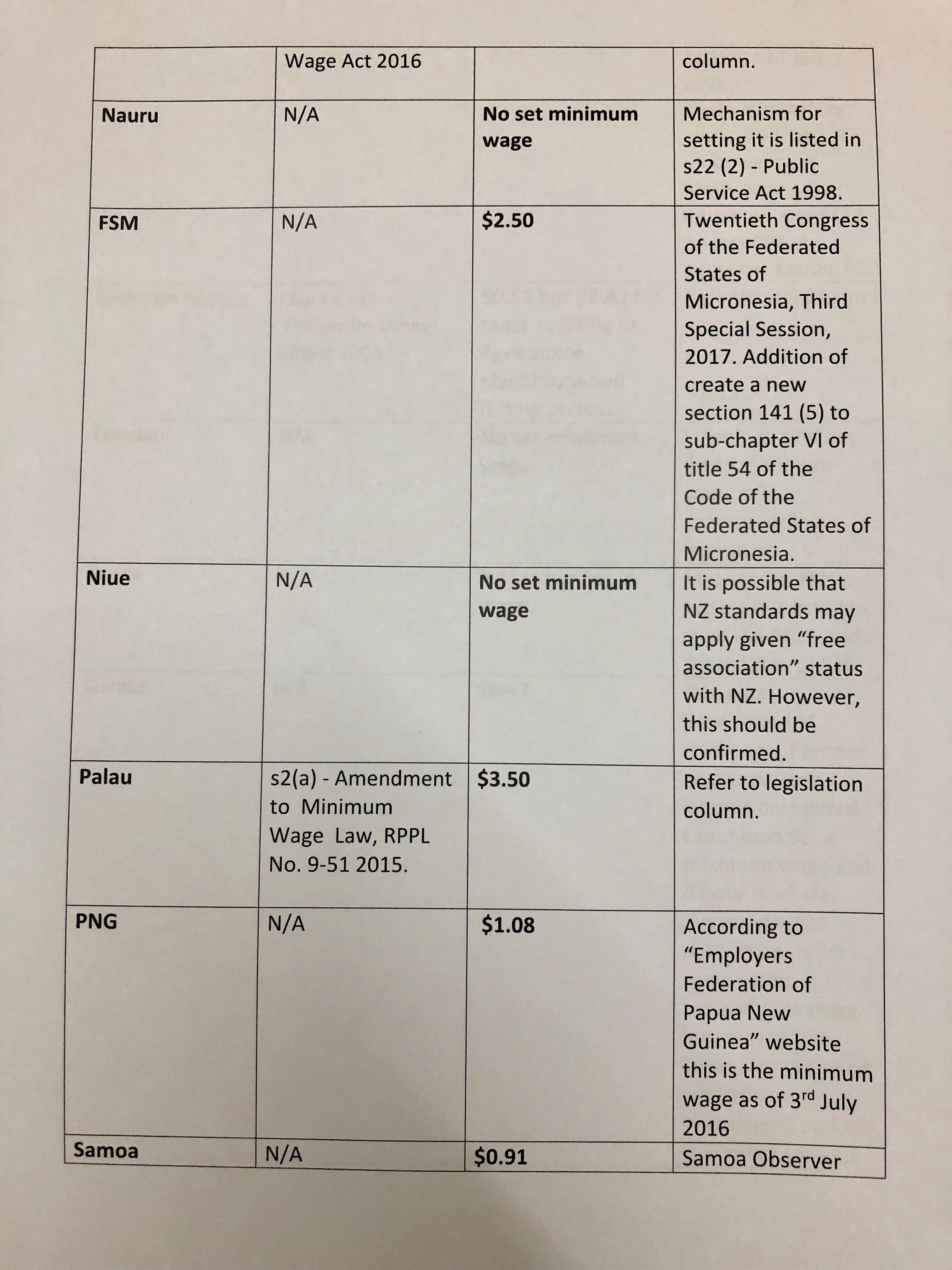

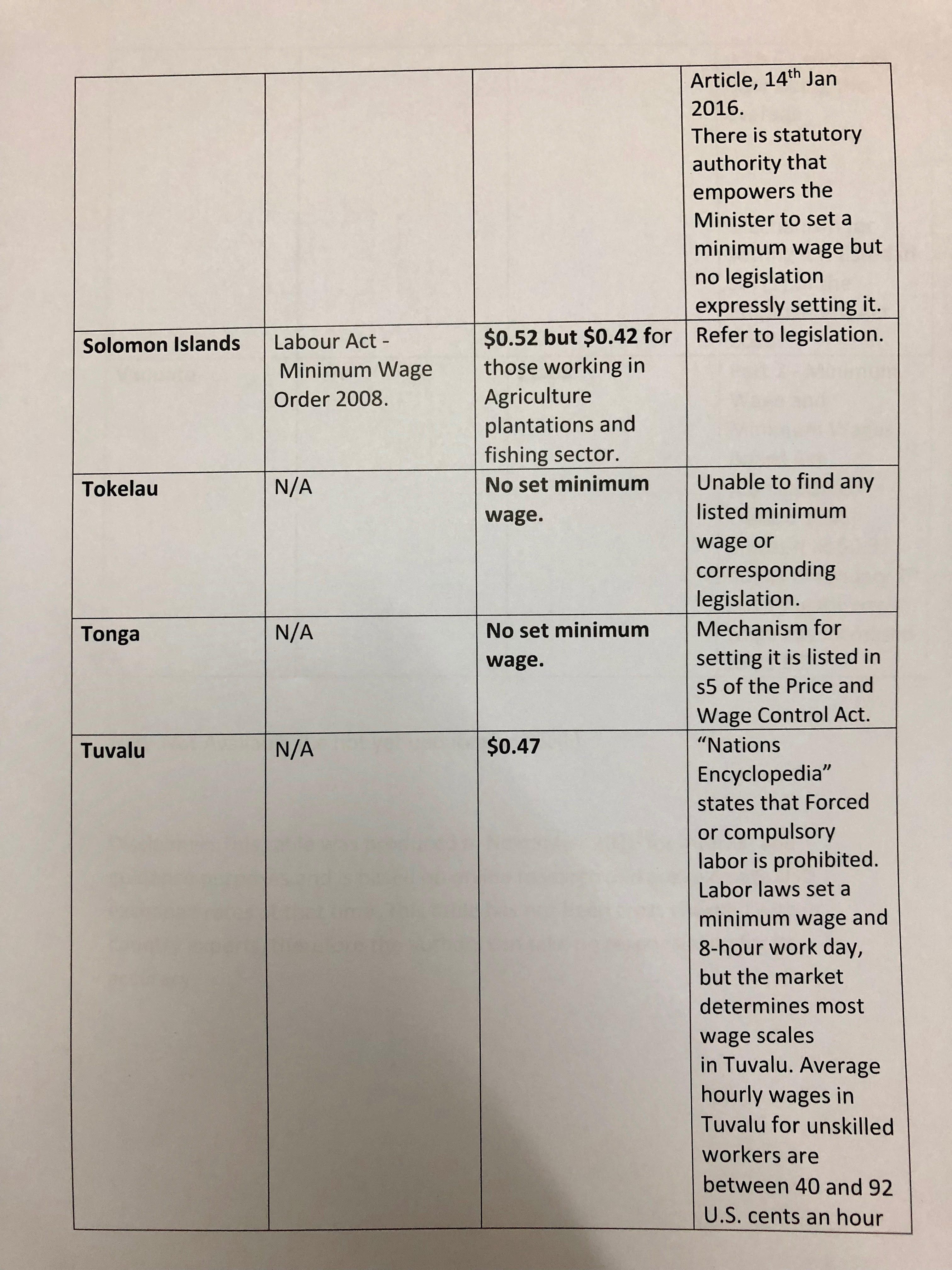

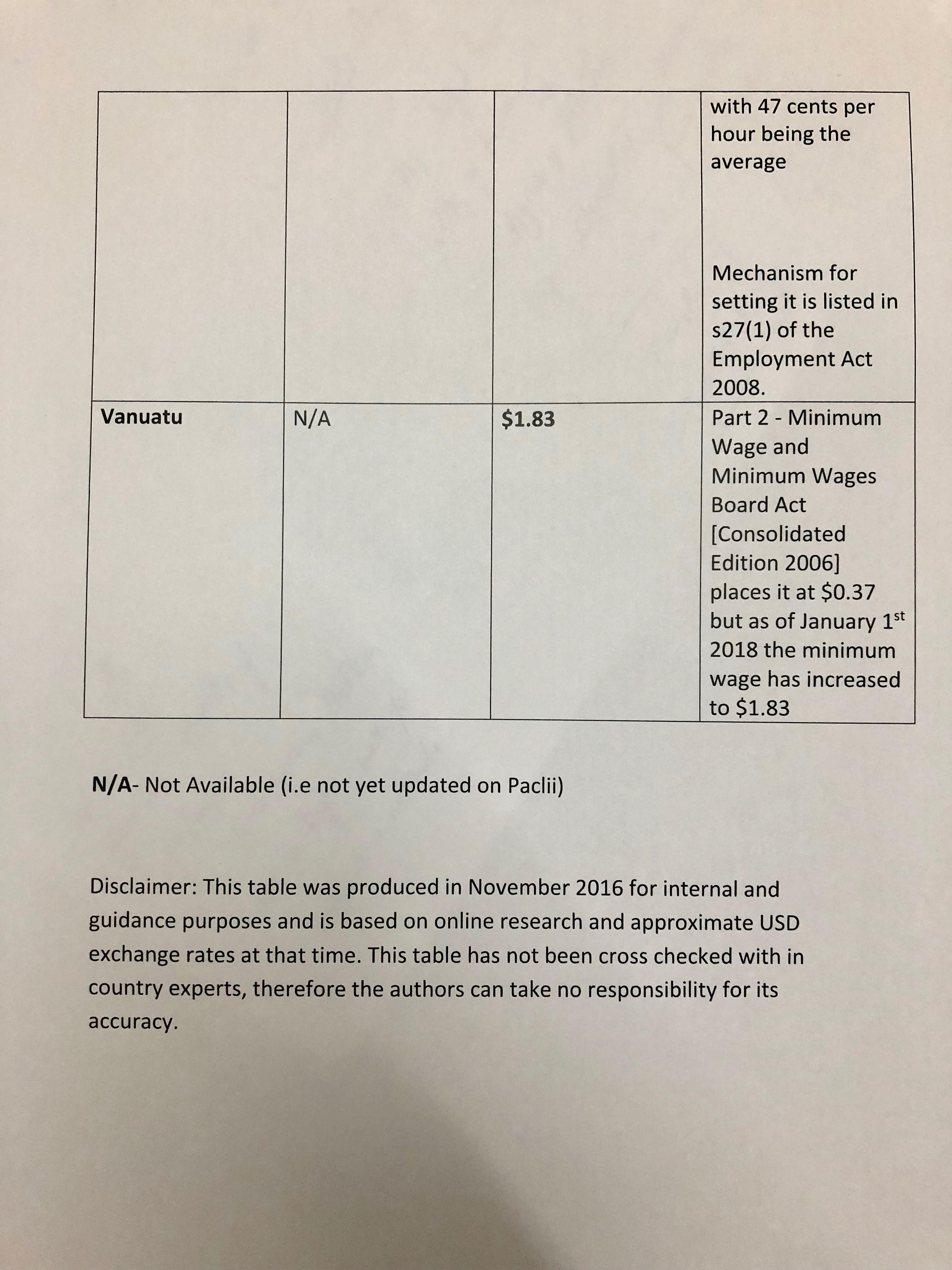

Across the Pacific Island jurisdictions, minimum wages are variable and not particularly high when compared to countries in the developed world.

In late 2016, an intern in our firm (Mr. Curtis Fatiaki who is now a law graduate of the University of Canterbury and going through his professional exams in NZ) looked at this issue and produced the following table that provides some information of minimum wages across Pacific Island jurisdictions:

While unemployment and exploring interesting opportunities also explain migration from the Pacific, when the minimum wages are compared with what Pacific Islanders may earn elsewhere, it suggests Pacific wages are likely to be a driver of migration to certain countries.

How is outgoing labour migration regulated under Fiji law?

Turning to Fiji law (apologies as we did not have time to consider all the laws of all Pacific jurisdictions), Fiji wants to regulate its citizens who may travel to work in other jurisdictions. On paper this is a strongly regulated area with section 37 of the Employment Relations Act ("ERA") requiring all written contracts for overseas work to be approved by the Permanent Secretary of the Ministry of Labour.

Further, recruitment agents must be registered in accordance with a process in Employment Agencies Regulations 2008. The recruitment agent must be a natural person and must deposit a $20,000 bond as part of the registration process. Agents fees may be regulated and approved by the Permanent Secretary.

Section 37(4) of the ERA creates a criminal offence as follows:

37 (4) No person shall enlist or recruit any person for employment under any foreign contract of service unless the person is authorised in writing by the Permanent Secretary.

37 (5) A person who contravenes subsection (4) commits an offence and is liable on conviction to a fine not exceeding $20,000 or to a term of imprisonment not exceeding 4 years or both.

Recently, in Fiji there have been a number of high profile reports regarding recruitment scams with groups appearing to target villagers in more remote areas with promises of jobs overseas. Fortunately, these groups have been reported and anyone interested in employing anyone from Fiji as either a potential employer or agent, should be aware of the offence in section 37 of the ERA.

Fiji's National Employment Centre

Fiji's National Employment Centre ("NEC") is set up under the National Employment Act to establish a foreign employment service.

Fiji's National Employment Centre aims to safeguard the interests of seasonal migrant workers from Fiji to other jurisdictions

The NEC mostly facilitates unskilled workers from Fiji to work abroad. While there are some plans to introduce medium skilled programmes, the focus is on unskilled workers because Fiji, in common with other Pacific Island jurisdictions, faces challenges retaining its own skilled essential workers like nurses and teachers.

The NEC works at a government to government level with MOUs signed between Australia and New Zealand (at present) that govern how the seasonal workers programmes are implemented. They also assist with some recruitment around the Pacific including a retired teacher programme.

The NEC does not regulate private recruitment, and section 37 of the ERA (above) applies. The NEC will only work with approved and registered recruitment agents, of which there are currently 3 in Fiji.

In terms of the regulation/due diligence on the Fiji side the NEC, amongst other things:

- conducts pre-departure training with Fiji workers in relation to culture, behaviour and what to expect

- if the worker is from a traditional Fijian village this also involves the Turaga-ni-koro, meaning that any errant behaviour means - you’ve let down not just yourself - but your whole village!

In terms of regulation/due diligence on the Australia/NZ side - all employers must follow their State's labour law and issues should be followed up and necessary action taken. The Australian/NZ employer provides its stipulations regarding the work and workers that are required and the NEC then looks to meet those needs.

At present, the seasonal work involves fruit picking but we are informed that there could be more interesting prospects in future. After all, workers in Fiji and other parts of the Pacific have much to recommend them, including but not limited to: good standards of education, English speakers, and high levels of natural ability/capability.

How is inward migration regulated under Fiji law?

For inward migration, again section 37 of the ERA applies and amongst other things, requires that the contract must be in writing. With inward migration other government departments will be involved including Immigration.

Depending on the work and scale of the project (is it govt to govt?) Immigration works with other government agencies like Ministry of Foreign Affairs to facilitate government to government MOUs.

Fiji, and Suva in particular, also has a large numbers of big International and Regional Development/International Agencies, DFAT funded projects, and INGOs that generally operate on the basis of MOUs with government and have large numbers of workers who are from outside the Pacific Islands.

The government to government MOUs will set out the terms that are agreed in terms of number of workers that may come to Fiji for the purposes of the work or project. The information regarding numbers of workers in Fiji on this basis does not seem to be currently available (and this may be the same in many jurisdictions).

But the point is, it is difficult to understand how many of these workers from overseas continue to work for their own State in Fiji and are therefore not "migrant workers" under the Convention and may not be subject to the laws of Fiji, and how many are migrant workers subject to Fiji laws and regulation. The designation of the individual worker will also affect his or her immigration status and whether their working status is "exempt" or whether he or she is required to have a work permit.

However, migrant workers employed by a Fiji employer and who are on work permits and their employers are subject to Fiji's laws and jurisdiction, including employment law.

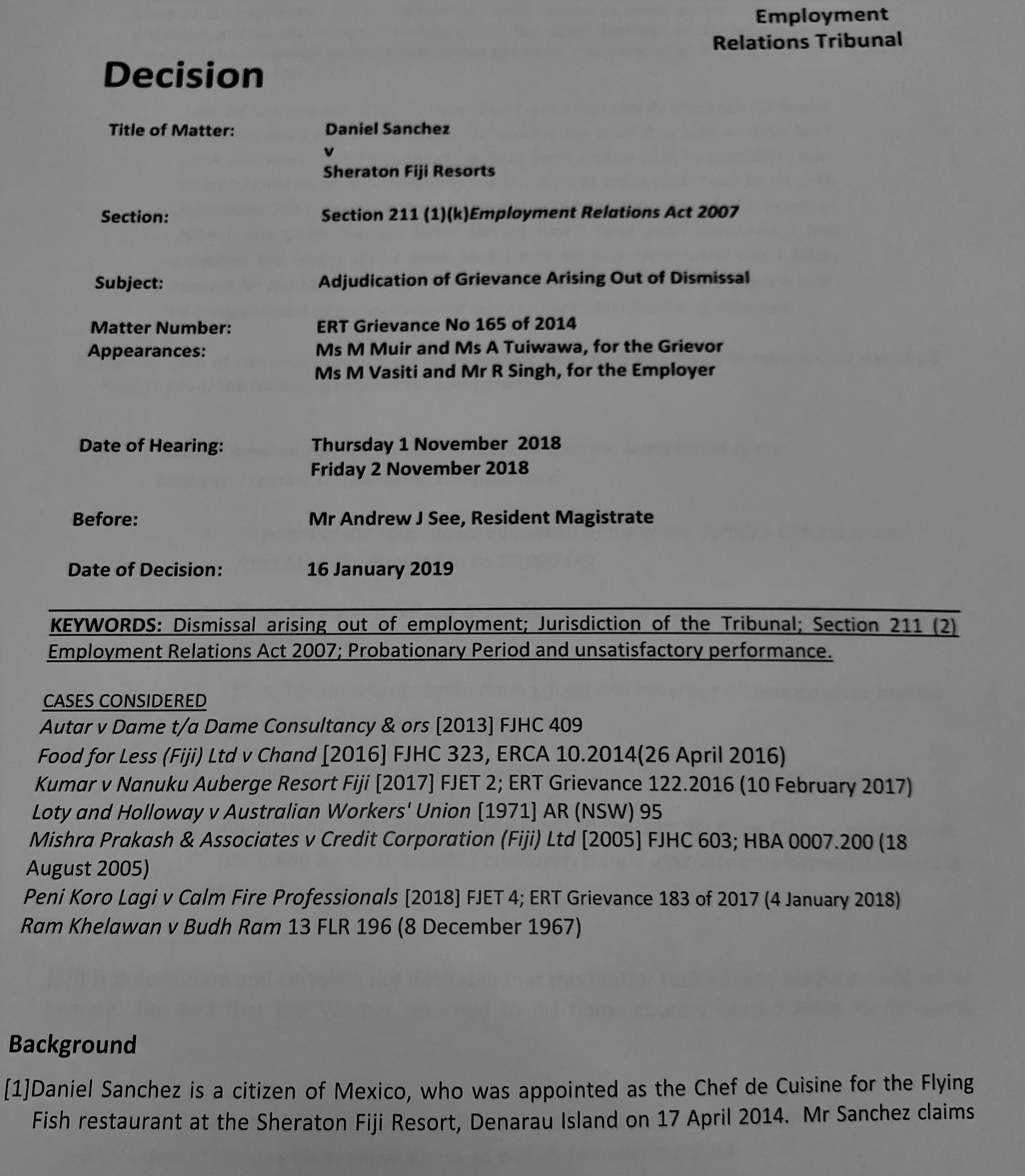

The Employment Relations Tribunal recent decision in Daniel Sanchez v The Sheraton (16 January 2019) demonstrates that the employment contract is paramount and that Fiji's law relating to termination of employment will be applied to the employer. In brief, Mr Sanchez was from Mexico and recruited by an agent of the Sheraton resort on Denarau Island to work in a restaurant known as the Flying Fish Restaurant. Mr. Sanchez is a chef and was employed as a chef but then he was terminated from his employment after just one month. The Employment Relations Tribunal awarded Mr. Sanchez $37,760 for 5 months wages and relocation allowance - because the hotel/resort had not followed its own disciplinary procedures in terminating his employment.

The Tribunal provided relevant guidance for international labour contracts and provided useful guidance to employers and employees in this situation who should - before concluding the employment terms and conditions specifically consider the:

- length of the contract that they are entering into (whether or not it is for a fixed term)

- circumstances for how an employment contract can be terminated prematurely

- relocation arrangements (whether this will include insurance and housing allowance)

- an adjustment period for change.

For more information relating to the Sanchez case, please see our earlier commercial law update: here

Migrant labour and rights/freedoms is ultimately a question of jurisdiction - this makes Pacific Fisheries such a difficult issue

The concept of legal jurisdiction is at the heart of all migrant labour issues. It is jurisdiction that will determine both the rules that apply and how they are enforced (regulation). For migrant workers, they are submitting to be regulated by the jurisdiction in which they work. This is why some migrant labour schemes can run into difficulty.

When something goes wrong - whose jurisdiction's employment laws apply? Generally speaking, it will be the laws of the jurisdiction in which the work is taking place. This is why providing accurate information and stopping the use of inaccurate or misleading information is so vital to protect migrant workers and their families.

In terms of Fiji and the Pacific's fisheries there is a problem of jurisdiction that contributes to denying Pacific Islanders more of a share of the benefits of their fisheries resources that if well managed are renewable and valuable.

It is currently estimated by the Pew Foundation (here) that Pacific tuna is worth US$22.7 billion per annum, with approximately US$12bn paid to fishers globally. The Pacific Island Countries have the exclusive rights, in accordance with the United Nations Convention of the Law of the Sea (LOSC) to harvest tuna (or licence others to harvest tuna) in the large areas of oceans known as Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs).

However, within these large Pacific EEZs, Pacific Islands have sovereign rights but not sovereignty. Therefore, Pacific Islands cannot regulate employment conditions on the boats that harvest the tuna while they are in these areas of ocean, as these conditions are ultimately regulated by the State to which the fishing boat/vessel is registered. Frequently, fishing vessels are registered to States that do not regulate or care about the working conditions on the boats and there is, therefore, no effective jurisdiction. This leaves workers on those boats vulnerable to exploitation, and appears to be an issue that the Convention did not anticipate.

Pacific Island leaders do not want to expose Pacific Islanders to dangerous and harsh working conditions and it therefore denies an employment opportunity and more of a share of the resources.

The onus is on other States in the Asia Pacific region to do more to regulate their fishing vessels and collaborate to lift employment standards for Pacific Islanders.

Conclusions

Migrant workers and their families are vulnerable and Fiji and other Pacific Island Countries may, at some point, be well advised to ratify the Convention in part to provide a message regarding how Pacific Islanders should be treated while working in overseas jurisdictions.

Any foreign employer or agent representing a foreign employer who is interested in recruiting Fijians to work overseas should consider the requirements of the ERA and consult with the Ministry of Labour, and in particular the Permanent Secretary.

Given the lack of consistent employment standards across different legal jurisdictions it is important for all jurisdictions to collaborate and ensure for migrant workers that they are aware of their rights before they arrive in the jurisdiction they want to work in. Ultimately, laws may provide some protection for migrant workers, but it should also be remembered that enforcing those legal rights can also be difficult. For example, the Sanchez case still took 4 years to reach a final determination.

With thanks to:

The Fiji Law Society and all the committee members of LAWASIA for arranging the excellent LAWASIA Employment Law Forum, 25-26 January, 2019 in Fiji!

and

Fiji's National Employment Centre for providing the time to meet with them to discuss their work - a friendly and informative meeting indeed - thank you!

For more information on LAWASIA please see here

Please note: Fiji's Parliament voted on 16 May 2019 to become the first Pacific Island jurisdiction to ratify the Convention, this is the report from the Fiji Times, 17 May 2019:

This commercial law update is provided for general information purposes only and is not, and should not be relied upon, as legal advice.