Risk Allocation

This commercial law update looks at the principles behind efficient risk allocation in a contract and how, a lack of understanding of these principles, might lead to unintended consequences.

Every contract is essentially a sharing or allocation of risk, responsibility, and reward between the parties. It is not sufficient for commercial lawyers to rely on template contracts or checklists because to understand and assist with a commercial transaction requires an understanding of the risks involved. A thorough understanding of risk will assist with the provision of informed legal advice and a contract that may avoid, reduce or fairly allocate risk.

This legal update considers the key questions that arise in terms of the allocation of risk: how should the risks be shared? Is there an efficient way of sharing risk? What considerations should be taken into account when deciding which party should take on which risk in a contract?

How risk is shared impacts directly on the price of services or goods provided under the contract and, in materially adverse circumstances, could even result in the consequences of the risk being suffered or shouldered by a party other than the party who agreed to shoulder the risk under the contract.

The commonly held view that all risk should be placed on one party (usually the party supplying the goods or the services) because it is getting paid for those goods or services is an over-simplification. Each risk needs to be assessed on its own merits.

Especially in construction contracts (due to the nature of the contract and the inherent risks in those contracts), there are direct project cost benefits that can be realised when each risk is assessed and the allocation tailored to the particular project.

Risk motivates parties to act so as to manage or minimise those risks. However, if the allocation of risk is not managed well, it could even motivate a party to deliberately breach the terms of the contract.

It is very important therefore that, when negotiating and drafting a contract, the parties (and the lawyer involved) understand how risk might impact on the commercial aspects of the contract and the motivation of the parties involved, and that they understand the principles behind how to efficiently allocate risk between the parties to a contract.

What is Risk?

Risk can be simply defined as the source of uncertainty in achieving defined activities or objectives.

Assessing Risk

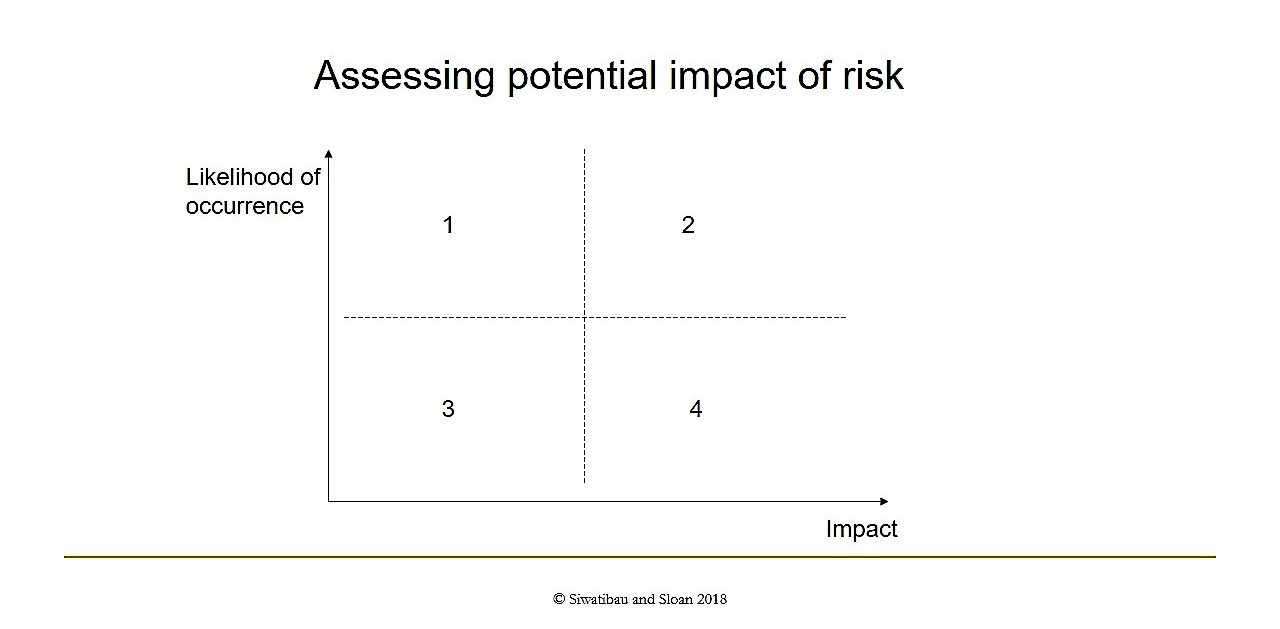

Risk can be assessed based on the likelihood of occurrence and the potential impact.

For example:

Dealing with Risk

Once a risk is assessed in a project, the question then arises, how should we deal with this risk?

This can be distilled down to 4 steps, expressed as questions:

1. Can the risk be avoided?

For example, can we undertake the project in a different way, or even don’t undertake the project at all?

Example: in the case of an acquisition, can restructure acquisition, carve off part of the business that you don’t want to purchase. Can we change the structure from a share purchase to an asset purchase?

2. Can the risk be reduced?

For example, if due diligence in a business acquisition deal turns up a short term lease contract on a key property, can we get the vendor to enter into new contract with longer term before going ahead with deal?

Example: Before we purchase a company, can we get the vendor to clean up its IP licences, ownership, royalty agreements, etc as part of pre-conditions of purchase?

3. Can the risk be absorbed?

If the risk can’t be avoided or reduced, can it be absorbed if it occurs?

For example: a common risk in a business acquisition is that of key employees leaving their employ with the target company. How best can the purchaser absorb this risk? What measures can the purchaser put in place to absorb this risk?

4. Can the risk be transferred?

If the risk can’t be avoided, reduced, or absorbed, then the next question is, who is the best party to allocate the risk to?

Allocating or Sharing Risk

Once the parties have decided to transfer the risk, the question now becomes one of risk allocation. Basically, how can we best allocate risk between 2 parties?

Risk allocation can be distilled down into 4 principles.

Principle 1:

The extent to which the consequences of a risk are allocated to a party should take into account the overall effect on that party’s business, both positive and negative

The extreme of this rule is not to allocate risk to a party where that party would be unable to deal with the consequences if it occurred.

For example: If a contractor were to be allocated all the risk of an extreme inclement weather event, where the consequences of that event (if it were to occur) would be to bankrupt the contractor’s business, then, if that event occurs, the contractor would be unable to rectify its consequences, and the consequences would then fall squarely back onto the other party to the contractor.

Whether the risk is controllable or not, this first principle should be the starting point when considering how to allocate and share risk.

Principle 2:

Risk should be allocated to a party in proportion to the extent to which it can influence the likelihood of that risk occurring

Basically, the party that can best prevent the risk occurring should have a sufficient stake in its consequences so as to motivate it to do just that.

For example: A company selling its business with an underlying short term lease, is in a better position to negotiate an extension of its lease agreement with the landlord than the purchaser and should be motivated to do so under the contract.

Principle 3:

Risk should be allocated to a party in proportion to the extent to which it can minimize the consequence if that risk occurs with all things being equal the second principle taking priority

Why should the second principle take priority? Because prevention is better than cure. It encourages a proactive approach to managing risk rather than a fire fighting approach.

Principle 4:

For minor risks, clarity of allocation should take priority over other principles

If the risks are clearly allocated, they can be simply priced into the equation and then whichever party has responsibility for those risks will be motivated to take all steps to minimize probability and/or impact of those risks in order to “save” money.

The other point is, if minor risks are not clearly allocated, just the administrative time and expense of dealing with each minor risk will be out of proportion to the impact of those risks.

Conclusions

A good understanding of risk is essential for commercial lawyers. While protecting our clients' interests is a paramount concern, there is little benefit if a contract unfairly allocates risk to the point that the commercial enterprise will fail.

It is also important to understand the connection between taking on greater risk and the cost of the goods or services increasing to reflect the allocation of risk.

A commercial lawyer's role therefore extends beyond simply recording the parties' intentions but should include explaining the commercial risks that are involved and how those risks can be fairly allocated to support the parties commercial intentions.

For more information on allocating risk in commercial contracts or for any other commercial law enquiry please contact Atu Siwatibau: atu@sas.com.fj

Please note:

This commercial law update is provided for general information purposes only and it is not, and should not be relied on as, legal advice.